An Attic in Prague, 1939

Most of us can never contemplate death like this.

This short story, published in the latest print issue of Locust Review, is behind a paywall. Meaning that the only ways to read it are purchasing the latest issue, or becoming a paid subscriber here at That Ellipsis… Luckily for you, yearly subs are 25% off for the month of October. off a yearly subscription. That’s 40 dollars for a yearly subscription instead of 50. Even better, those who opt for a Founding Member subscription will get a half-off price, paying 100 up front rather than 200.

Even in this cacophony, it’s the silence that unsettles most. If only because it won’t be long until it’s pierced again. Screaming, shouting, tires screeching, panicked footfalls, sporadic gunfire. If there were ever a silence that could threaten, a kind of quietude that, for a few seconds or several minutes, promises to split the skull of whomever steps in its way, this is it.

It was the silence that told us this night was coming. The things we said to ourselves in the hope that the dread will quiet. They’ll never come to Prague, we assured ourselves. They only want the Sudetenland. But in between, in that small pause, we could hear the coming years screaming at us. And we knew that there would be hundreds of thousands, in fact millions, who would never live to know how empty our reassurances were.

I would be lying if I said that I think this will work. That this mythical mound of dirt could somehow come together and move, let alone keep Josefov safe. I can’t even say what it is that draws me here now, except the knowledge that everything else has failed. The facile words of Beneš, the blinkered confidence of the Communists, the pious promises of rabbis whose words I started dismissing long ago.

When I heard that the Wehrmacht had reached the outskirts of the city, I froze. Out of fear? Frustration? Despair? Who knows? Whatever it was that bolted me to the floor, I could do little more than stand in front of my window, my eyes glazing over as panicking people ran in and out of my sightlines.

The only thought I could make myself think all the while was that this was always going to happen. Nations are as finite as they are fleeting. The last war, and countless before, taught us this. Still, that this one could vanish into thin air, that it can cease to exist, as this one will for the next several years, is enough to leave you forgetting to breathe.

Only when they had taken the city’s center, marching down Wenceslas Square, was I finally jolted into motion. It wasn’t thought that moved me, not even instinct. All I knew to do was run in the direction of the Altneuschul, of that building I hadn’t entered since my teenage years. When I burst through its doors, I had no idea where I was going. Only that within seconds I was racing up a staircase I had never noticed before, through the doors to an attic I had only heard about.

And still I didn’t expect the legend to be true. Myths and fairy tales are a child’s things, and I put them aside a long time ago. When I saw this table, mounded with dry and cracking clay, for several minutes I could only stop and stare, mouth open, at this proof that the stories were real. Real as my breath, as fire, as the gunshots outside, as the barking of German orders echoing down the narrow streets. It was those sounds that brought me here, when all other options from kind persuasion to armed force have disappeared, when myth is all we have left.

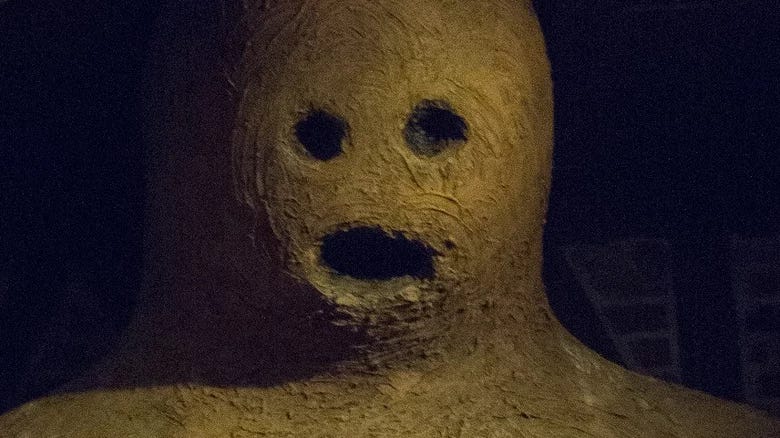

Most of us can never contemplate death like this. We tell ourselves that it isn’t the rational thing to do. What really prevents us is fear. Pure, simple, and abject. That idea that something may become nothing. But three hundred years ago, the Maharal – though he could not have been the first – reversed the sequence. He molded these arms and legs thick as tree trunks, this squat head, this hulking torso. And he alchemically converted the inert into the moveable, the dead into the spirit, the truth of survival, adding to a throughline that endures through centuries of shapeshifting Talmudic bickering.

And yes, I know very well how those stories ended. The bloodshed, the heartbreak and homes destroyed beyond repair by the very thing that was made to protect us. This pile of dirt in front of me is capable of ghastly, wonderful things. Every time it crosses the border between dream and nightmare, it becomes a bit more real. Until it arrives here, laying on a table right in front of me.

Perhaps we can only look these gruesome truths in the eye at our most desperate, when we’ve put aside all the reason and the urge to explain that we’ve cribbed into our minds, rationalizing away the mystical happenstance that lets bad things happen to good people. Maybe we don’t have to understand. Maybe teaching ourselves the logic of the unknowable is less important than opening up to its wondrous terror, stilling ourselves, more and more, until we can feel it resting in our bones. To hear, in the terrible quiet, what lies on the other side in all directions. To know that survival is less about a collection of individual lives, and more about the extramundane trajectory of history you reach for.

Three years down the line we’ll hear of those in Warsaw. Knowing they were assured death, they will figure it better to die human, facing the monster that shoves them into hovels and forces them to march toward a quiet and degraded end. That’s what this is. This anguished, undefeated realization that we can no longer ignore the option of death.

Perhaps this loam giant, this man-made half-man, this – let us say it… golem – will do what it did last time, rampage through our streets without anything like discrimination. But it may also keep its own word, the promise implied in its creation, distinguish between those who need protection and those who need to die in order for that protection to be provided. It is rarely so clear cut. But while I carve an Aleph into this hulking thing’s forehead, undoing the erasure of three hundred years ago, turning “mét” to “emét,” I can only hope that my own blurred, incomplete view into the future proves itself out.

Decades from now they’ll tell more legends and myths, more whispered tales about the Gestapo officers who tried to enter this attic. Some will say that they were sent there by Hitler himself, his occultist proclivities egging him on, perhaps with some endgame of harnessing the Kabbalah for the aims of the Reich. Others will say that it wasn’t the Gestapo, but simply two stupid soldaten who let their youthful curiosity lead them up here, seeing if the legends were true.

Either way, be it Gestapo or Werhrmacht, on higher orders or simply wandering dumb, they’ll never leave this attic alive. They’ll be torn limb from limb. The final thing they see will be this clay ogre’s massive foot caving in their skulls as they howl like babies for their mothers, trying to reach for their revolvers with arms ripped from their sockets. Two fewer Nazis, and with them, maybe a few more lives – of Jews, of socialists, of vagrants or queers – spared.

What the stories will forget, is me, that third man. The one who can hear them racing up these forgotten wooden steps right now, barking German at each other. That one Jew, that one man, that one human who, knowing he was facing oblivion, grasped the cosmic hubris that keeps one free.