The rake of progress is devious in London. There’s a full 2,000 years of history here, and much of it has been bulldozed. But there are enough examples of 300, 700, 1500 year-old structures still standing, places the rake has purposefully dragged around. Not so that they can be remembered, their layers of history comingled with our own, but so they can be flattened and recontextualized, their events made safe and predictable.

London’s hidden architectures, its neglected spaces begging to be reclaimed from the bottom up; most are, predictably, smoothed over. Like New York and Paris and most other Euro-American metropolitan hubs-turned-tourist-traps, what made London a city of difference and discovery has been turned into a copy of a copy, easily integrated with the Costa Coffees and “Keep Calm” t-shirts.

Still, there is something vibrating under its winding streets, something that can’t be erased, vibrating underneath the layers of anodyne. Something that still allows works like From Hell or the zine visions of Laura Grace Ford to land, to strike the reader with uncanny familiarity. One gets the sense that, were the word “psychogeography” not coined by the Lettrist-Situationist set, it would have come to be called something more British in tone.

There are pitfalls in designating one’s self as a psychogeographer, particularly regarding social class. Experiencing a place, pondering its angles and contours, it is tempting to feel as if you are somehow discovering it. The fact is that you are simply feeling what countless others have felt before. The rub, the wrinkle, is that what we feel is obscured by how we are taught to think about our built environments. Or, perhaps more accurately, the way we are taught to not think about them. To take them for granted, to accept them as mundane, to assume them as alienated.

Always implied here are two unasked questions. Who builds the built environment? And for whom is it built? On the surface, these are straightforward questions, but the experience of Broadwater Farm in Tottenham highlights how complicated their answers can be.

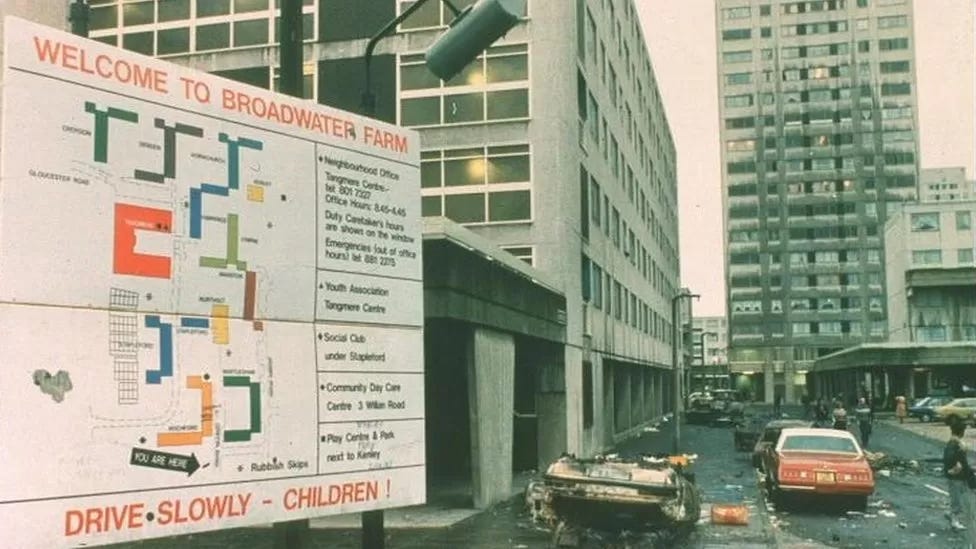

So much has already been observed and written about Broadwater, including by its residents. Still, it is difficult to walk through the estate and not be impressed by its utopian ambition. Even with the original futuristic raised walkways long gone, you can see its practical humanism borne out in the estate’s shape. Large towers and greenspaces at Broadwater provide thousands not just with housing, but with the possibility of connection and social cohesion, building blocks of what is nebulously called “community.” Playgrounds, a nursery school, an employment office, a community center.

Then there are the murals. Three of them. All were commissioned in the wake of the notorious riot that gripped the estate in 1985, and created by residents of Broadwater. One, on the side of the Rochford tower, depicts John Lennon, Bob Marley, Gandhi, and Martin Luther King in a bucolic scene. Another depicts a waterfall on the side of the Debden building. The third is a mosaic. It’s more abstract, but clearly communicates a vision of harmony and peace.

Murals like these flourished across London in the 1980s, funded and encouraged by the city’s left-wing Greater London Council before it was abolished by Margaret Thatcher. Owen Hatherley calls these murals “the capital’s last surviving remnants of municipal socialism.”

It is also difficult to ignore Broadwater Farm’s location, right next to the absolutely gorgeous expanse of Lordship Recreation Ground. The juxtaposition between concrete brutalism and verdant idyll brings to mind all manner of leisurely possibilities, long airy walks with friends and kids’ football games without having to trek to another neighborhood.

But letting your eyes focus past the shapes of the towers, homing in on the corners of mundane disrepair, noting the heavy presence of CCTV cameras, and the unavoidable ongoing demolition of some of the tower blocks; all reveal how easy it is for places like Broadwater to be used as a human warehouse, a facility for social control and systematic deprivation. Different moments and image layers bleed into each other, each permutation a new trajectory. Understanding this jumble can only be accomplished — appropriately, and like so much else in the apparent futurelessness of late capitalism — by looking at it out of order.

Middle-ground: the human dump

The broad strokes of the Broadwater Farm riots are a part of Britain’s collective memory. In October 1985, London Metropolitan Police kicked in the front door of Cynthia Jarrett’s flat. Jarrett didn’t live at Broadwater, but her son Floyd did. Floyd had been arrested earlier in the day, and the cops decided his mother’s home was fair game.

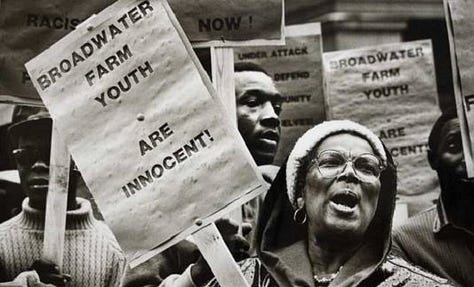

Cynthia had a heart attack from the shock and died on the spot. In the days following, the estate’s Black and Afro-Caribbean residents erupted in an all-out rebellion against the cops. A local newsagent’s shop was set on fire, dozens were arrested, and one police constable — Keith Blakelock — was killed. Three residents — Mark Braithwaite, Winston Silcott, and Engin Raghip — were later convicted for Blakelock’s murder on specious evidence. Two were released after four years, following a public defense campaign. The third was finally released in 2003.

Though Broadwater wasn’t the catalyst, by the end of 1985 there had been similar eruptions across London and the UK. Brixton, Peckham, Liverpool, Birmingham. Yes, these rebellions were primarily a response to racist police violence and intimidation. Yes, police and state violence is often the most unmistakable and pointed manifestation of racism. A government inquiry explicitly insisted that policing, not housing, was at the root of the uprising. But we would be careless to dismiss the role that the more quotidian instances play in compounding the experiences of racialization and oppression. The contours of daily life, lived in constant reminder that this country will always view you as “less than.” These unavoidably tie in with heavy-handed policing, always the sharpest edge of contemporary racism.

One resident, interviewed years later, said that the local housing authority had come to view Broadwater as a “dumping ground,” a place to house the citizenry a crumbling empire would rather not regard. The buildings at Broadwater and their units were poorly maintained. Leaks and faulty electrical went un-repaired. There were rats and cockroaches. The crime rate was high, but the heavy police presence circling the estate was more concerned with harassing youth.

Organs that might have otherwise provided a way for tenants to fight back ended up further entrenching racial divisions. The estate’s Tenants’ Association deliberately excluded Black residents, and even white residents who might be associating too closely with their Black counterparts. One particularly wretched but telling moment highlighting this was a television appearance made by the elected heard of the association in 1974, where he voiced full-throated support for the National Front.

Not only did this disenfranchise residents of color at Broadwater, it effectively undermined white residents’ ability to advocate for themselves. Which, of course, is the point of racism: to redirect the inevitable pushback that comes from the downward pressures of systemic neglect.

Considering only this, it would seem that the “experiment” of social housing would be successful only if it aimed to shove the unwanted into the cracks of city life. That was essentially the argument, applied to social housing in general, made by Alice Coleman’s book Utopia On Trial. Released the same year as the Broadwater rebellion, its arguments were enthusiastically applied to the estate in its aftermath. By insisting that “lapses in civilised behaviour” were inevitable in these planned environments, Coleman was taking aim not just at the architectural foci of 1960s idealism, but the whole idea of housing as a public right.

No surprise then that Coleman’s words found resonance in Margaret Thatcher’s government. Any social provision, of any kind, will wither in a context where the idea of the social is anathema. Thatcher was already tearing away at the fabric of council housing through schemes like Right to Buy, setting in motion a process by which the number of publicly-owned residential units would decline from 6.5 million to just over 2 million.

Thatcher’s initial response to the Broadwater rebellion was predictable. Her advisors urged her to ignore calls for improved conditions on the council estates, claiming that better funding would simply end up in the “disco and drug trade.”

In the days after the rebellion, Bernie Grant, the Guyanese-born head of the local Labour-controlled council of Haringey, spoke in front of Tottenham Town Hall, describing the understandable anger among Broadwater residents. He was quickly denounced as celebrating P.C. Blakelock’s death. To demand a better life was clearly to encourage the enemy within.

Foreground: saving Broadwater

Eventually, the calls for more funding won out. An additional £30 million was plowed into Broadwater Farm in 1986. Concierge services were put in the lobby of each building to increase security and prevent crime. As one proponent put it, the effect of this was to ensure that the street started at the street, rather than at tenants’ front doors.

Improvements were also made to the environments between buildings, the courtyards and green spaces. Playgrounds were installed. In 1993, the aforementioned raised walkways were demolished. Long-needed repairs were finally made.

Then, the cruel twist. Land is money, and if people can live on that land, then any money spent on it inevitably raises the specter of seeing how much more money you can get back for the investment. A nicer, safer housing estate inevitably translates in the minds of modern London developers into other “opportunities.”

Tottenham, along with most of Northwest London, along with most of virtually every contemporary city, has had to deal with this kind of pressure. In some places, residents end up displaced, uprooted, scattered. In others, they push back. That’s why the Haringey Development Vehicle (HDV) scheme went down in flames.

Had the HDV succeeded, it would have been one of the biggest handovers of public facilities into private hands that London had seen since Thatcher. Housing estates, parks, libraries, schools, council offices; all would have had their management handed to a £2bn private fund. But in the wake of the Grenfell fires, when private management of public housing was under intense scrutiny, a movement of local Haringey residents was able to take on the HGV. In early 2018, the New Labour council head who had stumped for the scheme stepped down. Since then, the HDV plan has basically been on life support.

This hasn’t stopped life at Broadwater Farm from being uprooted under the guise of improvement and development. Two of the blocks on Broadwater were found to be structurally unsound in the wake of Grenfell, and have since been demolished. Residents were promised that their lives would not be significantly disrupted by rehoming. That has not proven to be the case across the board. At least one resident has been forced into financial ruin as a result of the demolitions and forced evictions. The looming question is whether residents will be allowed right-of-return to the new flats built at Broadwater, as they have been promised. Past and present residents of the housing estate, and Tottenham more broadly, have been organizing around exactly that.

Background: utopia is ordinary

Who builds the built environment? And for whom?

Who… As Coleman’s shady title suggests, the architects of Broadwater Farm were indeed driven by a utopian impulse. At least of a sort. There is much to say about Le Corbusier, how his designs were explicitly intended to head off revolution. If council architects were inspired by Le Corbusier — and perhaps shared his motivations — then the upheavals of 1985 revealed how, ultimately, architecture cannot stanch urban revolt.

Still, it doesn’t take much to see that there was something genuinely democratic in Broadwater’s utopian designs. The idea of a complex that can provide not just the comfort of dry and warm living quarters with all the modern conveniences, but grocery shops and newsagents, community centers, even schools; this is borne of a belief that life can and should have a meaning and, therefore, a sense of order at the service of making that life better.

Planned? Yes. Perhaps even orchestrated, to a degree, from the top down. But such a measure of comfort and accessibility also frees up time for residents to have greater participation in public life: advocacy, community, art, even something as simple (but foreign by our standards) as getting to know and trust one’s neighbors. It isn’t altogether unlike the impetus behind the 15-minute city, and can also be suited to the same ecological ends.

One has to remember the state of most working-class housing in London before these kinds of estates went up. These were crowded flats in old buildings, often improvised, leaky and damp, with no modern conveniences to speak of. Many didn’t even have running water. In light of this, the first wave of residents at Broadwater Farm were understandably quite happy with what the estate provided them. “We came from a house that was built in 1816,” said one of these early residents, “so when we first arrived here it was like a holiday camp. There were bathrooms, indoor loos, you didn’t have to go out in the freezing cold anymore.”

For whom… This is a thornier question. Or at least a more open-ended one.

Yes, the Tenants’ Association of Broadwater Farm was intractably racist, but this didn’t stop tenants of color from organizing along more equitable, democratic lines. Cynthia Jarrett’s son Floyd was a founding member of the Broadwater Farm Youth Association, which sought to provide an organizing and advocacy space for younger residents of color and their allies.

One of its leading members was Floyd Jarrett, and some have speculated that it was his visible advocacy that made him a target for police in 1985. Before the rebellions, the BWYFA had managed to successfully mobilize for basic services and repairs to be addressed. They had also managed to chip away at some of the bad reputation the estate had garnered as crime-infested and dangerous. More recent organizing — say, against the HDV, or to keep residents in their homes — clearly take a cue from the efforts of the BWYFA.

Walking through Broadwater today — winding between half-demolished buildings and those that still stand, watching residents come in and out of their residences, seeing kids play on the playgrounds — you can sense a tension between competing visions of the housing estate. The first vision is, of course, that of neoliberals and developers. It’s probably the most unmistakable. Naturally there’s no tolerance in this framework for anything smacking of equitability, let alone democracy.

As for what might provide a corrective to this hostile mode of life, these are fractured and refracted, corresponding to the different histories jockeying and bumping into each other in this estate. It’s more than a bit of a stretch to say that the utopian designs of Broadwater’s architects are what has motivated bottom-up organizing and rebellion among the estate’s residents, and not just because I can’t insist I know residents’ thoughts.

It would, however, seem appropriate to say that, whatever utopian impulse Broadwater’s designers had, they are incomplete and unrealized without their residents. No matter how high-minded or noble the aims of a building’s shape, it cannot be put into practice without the active engagement of those who live in it.

This is, it merits saying, an experimental process, and necessarily collective. Human substance often molds to its surrounding form, but sometimes these same humans force the form to yield. So much so that it cannot be limited to one housing estate. Governments, housing boards, property developers, police; these specialize in imposing confines. But history rarely regards them with reverence.

An announcement I’ve been sitting on for some time: Brazillian publisher sobinfluencia edições has translated my book Shake the City into Portuguese. If you read Portuguese, you can find more info here.