In the spring of 2017, I spent some time driving around the towns of Southern Illinois with Adam Turl, the first of many visits down to this area to visit with them. Alton, Belleville, Granite City; it doesn’t take long to drive between these places, and they often bleed into each other.

Turl is from this area. Driving around Southern Illinois, it was clear that they were more grounded and at home here. After spending most of their adulthood working as an editor and socialist organizer, Turl had started drawing and painting again, like they had in their youth. Much of their muse had been this region they knew so well and had seen so easily maligned. The devastation is real here: boarded-up shops on Main Street, neighborhoods where half the homes stand vacant, union halls trying to organize the last remaining steelworkers and miners against a slow tide of layoffs and workplace closures.

No doubt, it was a sometimes somber drive, even depressing at points. But Turl wanted to go to one place in particular. It was in Granite City, and it was a small, community-run arthouse, a residential home repurposed as a gallery, built into the empty spaces of a blue-collar neighborhood. There were murals, sculptures of plaster and repurposed metal, and small mirrors strung from trees, spinning in the wind and the light rain.

It was all profoundly out of step, but also exactly where it needed to be. It showed how a region that had been dropped into the crevices of history was suddenly capable of remembering itself without permission. It wasn’t just that it didn’t fit with the stereotype of these areas, the notions that people here are innately conservative and narrow, uncultured and ultimately without agency. It was the feeling that something nascent might awake – profoundly, drastically – from places like these. That if there were a way to revive the histories and stories so often forgotten in this part of the world, new possibilities might also emerge. Not just here, but in the rest of this drifting ship of a country.

Since then, Adam and their spouse, Tish Turl, have schlepped their way down to Las Vegas (where Adam taught compositional drawing after finishing their Masters degree) and back to Southern Illinois. While in Vegas, they started the Born Again Labor Museum, a weird, radical, unapologetic, constantly-evolving arthouse project that also sought to be a community for radicals, labor organizers, anti-racists, and others trying to push the forgotten back into the center of history. They also initiated a publication, Locust Review, whose ideas and aesthetics pluck at the same strange and militant themes. (It is also, perhaps not so incidentally, a project I worked with them in founding.) At the time of writing, Locust is about to publish its twelfth print issue.

There are, naturally, some who would scratch their head at the idea that an art space might aim at unearthing history, let alone redefining it. This gets to the heart of what makes art matter, however, why it is, as Turl says, a social necessity. “Art simultaneously reflects and transcends,” wrote Marxist musicologist Maynard Solomon, “says ‘Yes’ and cries ‘No’; is created by history and creates history; points toward the future by reference to the past and by liberation of the latent tendencies of the present.”

The Turls would, just as naturally, agree with Solomon’s assertion. When it was time to move back to Southern Illinois for Adam to complete their PhD and Tish to start their Masters in poetry, they brought BALM with them. Here, it hasn’t just soldiered on, but thrived, inviting all manner of organizers, creatives, and other weirdos into their fold.

Is the Born Again Labor Museum a labor museum? Or an art museum? Why is it “born again”?

Tish: I think that it's both. I think that it's an art museum. It's also a labor museum. It's a museum of struggle and people. Because just as much as it is about putting up our stuff, it's also about interacting with and being reverent towards the history of struggle and people because we love people.

The Born Again thing, I mean, obviously we're playing with evangelical language there. But to me, there's also just a really powerful… it speaks to a phoenix quality, to the fact that this struggle is forever. As long as there is a working class, we will consistently return to this struggle. It cannot be killed because of just the nature of it, basically.

Adam: It's a conflation of evangelical language and Marxist language, particularly the concept of dead labor and living labor – dead labor being the wealth that was exploited for previous generation of workers, capital, machines, and living labor being the current generation of workers. It was sort of inspired by Walter Benjamin and Michael Löwy, in particular Löwy’s teasing out [in his book Fire Alarm] of Benjamin’s use of the concept of apokatastasis, which is a theological concept about the redemption of lost souls. Benjamin is applying this to the revolutionary generation – particularly in his “Theses On History” – redeeming all previous generations of exploited and oppressed.

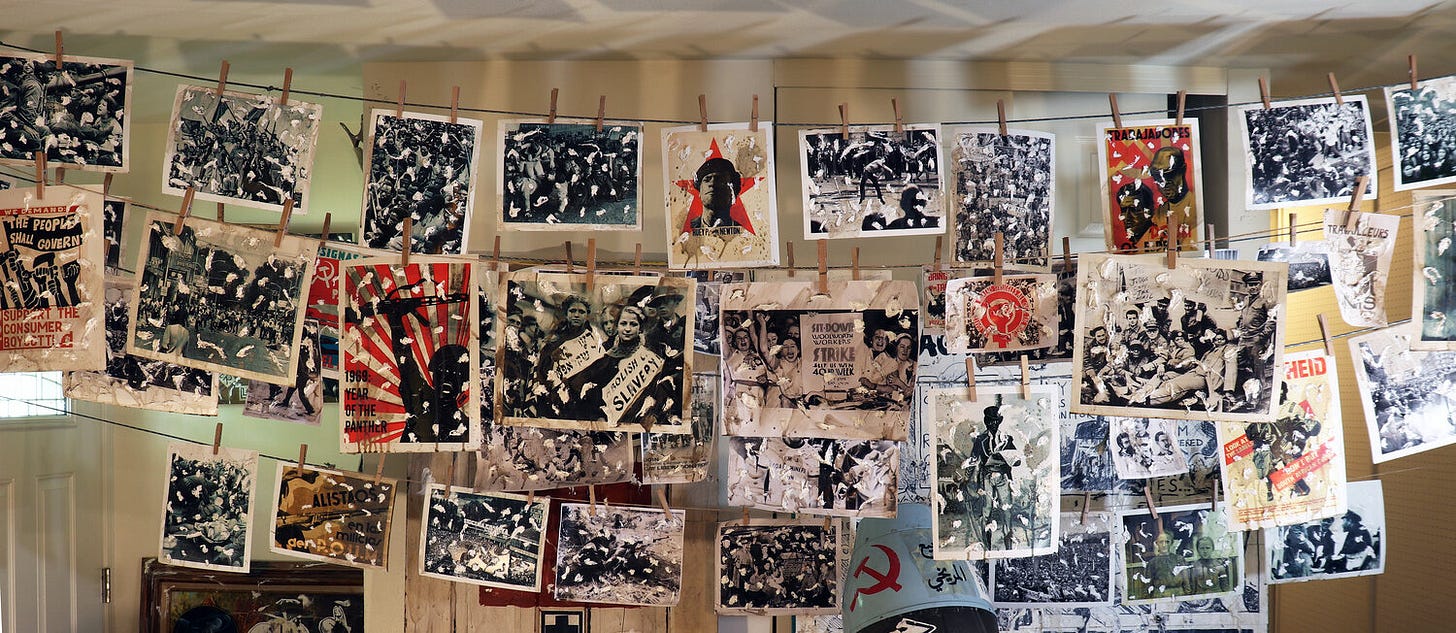

We started with this idea of counter-imaginary, against the imagination’s stultification in [cultural theorist Mark Fisher’s theory of] capitalist realism. What if everything could come back? And not just, you know, artifacts, or schematic histories of the labor movement, but psychologies, poetry, things like that coming back in the space. And it evolves and changes depending on what we're doing.

So what spurred the decision to start BALM? Why start it now and why does it need exist in a place like Southern Illinois in particular? You mentioned the sort of the apokatastasis and the lost souls out there. Is this a place that has a lot of lost souls?

Adam: I think every place has a lot of lost souls, but also there's the impossibility of representation. We're from here. I'm from this town, Carbondale, Illinois, and we're familiar with the nature of the loss here in a way we might not be intimately familiar with in other places. But the sort of impetus was this idea, like, from the realization the art space is a theatrical space.

We're more familiar with the nature of the lost souls here than perhaps other places, but the impetus was the art space as a theatrical space. See, when Benjamin talks about the cultic value of the art object, he's talking about the sort of social performance that surrounds the unique art object. And he gives the example of the sculpture in a church. You can look at other examples historically. What we saw during these protests in Boyle Heights [a neighborhood in Los Angeles] against the art galleries, and similar things happening in other cities, was the performance around these unique art objects was becoming gentrification. Whatever its content or gesture actually meant, the artwork was connected to this displacement of working class people and people of color. We didn't want to be a part of that. Instead, we wanted to the performance around our artwork to be solidarity with the working class and social struggle. We could tell that that was going to be difficult in a place like Las Vegas, where I was teaching at the university. It would be more possible to do that kind of thing here without contributing to gentrification and being a part of the problem.

Tish: I don't think it has to be in Southern Illinois. But we had to be in Southern Illinois. And the way that we wanted to push or the way that [BALM] was evolving, it just works better here.

And maybe... that would not necessarily be the case if we were still in Vegas or if we ended up somewhere else it would have evolved but yeah I mean this is just sort of the place it needed to be to not participate in that gentrification and I don't know I think like we're going to talk about I know how BALM relates to time and we've also you know Adam mentioned time being different for the working class I think that I think that the way things work here versus sort of the way things work temporally in Vegas, it just can feel like it's here. But the thing is that it worked in Vegas too, because it almost cut against the sort of immediacy. Anyway, yeah, just to reiterate, I don't think it needs to be in Southern Illinois, but I think that there is maybe something that connects it here. And it's probably just our history.

Adam: It doesn't need to be here, but it matters that it is here. It's part of the meaning of it that it's here. It would mean something different somewhere else, which could be good, it could be bad, or just different. Because everything around a work of art or a performance is part of the meaning of it. If you look at Picasso's Guernica, there's not really a lot in the painting that's clearly didactic or about the Nazis. But it was toured around to raise money for the Republican Army during the Spanish Civil War. It's been part of the anti-war protests. Its aura has accrued these meanings over time, right? And that changes the meaning of the work.

Places like Southern Illinois – whether we describe it as “rural” or “rust belt” or any other quick-and-easy term – are either described as political and cultural wastelands or just written off as “Trump country.” But that’s, at best, an oversimplification, isn’t it?

Tish: It is a frustrating oversimplification because I think that it forgets exactly what it is that… I think it does exactly what BALM tries to undo, right? When you wash areas like this with a broad brush like that, you're erasing all of the people who are being tortured by all those policies that get it called Trump country, right? Whereas BALM really wants the exact opposite of that.

Adam: I don't think it's an oversimplification, I think it's an ideological construction. And of course, ideology has some reflection of reality. Marx described it as reality upside down as in a camera obscura, referring to the sort of special device that painters used at a particular point in history to copy images. reality, but it would flip things upside down. And it's an ideological construction that is sort of passing judgment on spaces that have been suffering, areas that have been suffering under uneven by development, neoliberalism, deindustrialization. And it has roots in the othering of the poor that go back to colonization. This is where the phrase “white trash” comes from, for example, referring to people, starting in the Carolinas, who didn't get land because the plantation class took all the land. Until the 1970s, the ruling class and middle class conception of rural poor people was they were sexually indiscriminate and promiscuous and disproportionately queer. Sometime between the 70s and the 90s, it became flipped that working class poor people were, particularly in certain areas, were promiscuous, but also bigoted.

Now, of course, there's bigoted people and queer people everywhere, but the nuance didn’t matter. And it’s a notion that’s incredibly harmful. One of the reasons we got Trump in 2016 was Hillary Clinton refused to go to the Rust Belt – and probably couldn't go to the Rust Belt because of her relationship to the de-industrialization that happened there. These were places Obama won twice. Then Trump won, either because people stayed home or a handful of people switched over to vote for Trump.

In certain parts of the country that have been hit hard by deindustrialization or rural areas, and particularly the South, I think, due to unreconciled things, there are hangovers from Jim Crow and the Civil War. But the history and present here, just like everywhere else, is contested. In the 1930s, the Communist Party was very large in Southern Illinois, particularly among miners. In 1977, you had the miners' strike, in which we had mass meetings of people in towns in Southern Illinois to discuss how they were going to stop scab coal being brought in from the West. We had the 1970 student strike that shut down the university. The Black Panther Party house here in Carbondale was attacked by the police. The Panthers were arrested, of course, but they were acquitted by an all-white jury in the neighboring town, because people identified in that moment with the Black Panthers.

There was a massive strike among faculty at Southern Illinois University in 2011, where faculty beat back plans to repeal tenure, and where thousands of students walked out of class to support their teachers. I don't like boosterism, so I don't like listing off all the good shit that happens or bad shit that happens. But we also had one of the first local ordinances protecting queer and trans refugees from states that were passing anti-trans laws over the past two years. Our town also has a long history of punk houses. These have interpenetrations with the protests that have happened historically.

Every town has a culture, good and bad, right? I think what, in some ways, that story that comes from the ruling class about certain areas, certain people being irrevocably backwards, that story shifts. So to get back to the art, part of cutting against that narrative means trying to construct counter-imaginaries.

So why start an art museum? Why not just make propaganda? Or why not just hand out books or pamphlets?

Tish: Propaganda can itself be art. One of the things that I really love about BALM in relation to those things that you brought up is that we do hand out literature and do education there. The thing that is really frustrating about your standard art museum experience, which I know we've talked about before, is the removal of context, and the fact that everything is just so clean and separate. Having the art and the the books and the space and all of that together; that reinforces the meaning of it all. I think it's just a better space for it.

Adam: People should make propaganda and do those things didactically. But the short answer is I'm an artist and Tish is a poet. We're going to do those things because art is a human necessity that is both spiritual and existential self-expression. But it’s also social. So it's going to have a political aspect to it. You you can have a great piece of art that talks about the existential condition. But then it's undermined if it doesn't actually connect that to the social reality.

Self-expression is not equal for everyone right? The rarefied spaces of the art world, or – I was talking to some people about this the other day about how even the cost of going to music festivals is prohibitively expensive for larger and larger numbers of people. So these spaces get more and more rarefied. Art is a human necessity. You have to deal with the social aspect of it too and how that changes the meaning of the artwork too. Of course, people should do [propaganda and education]. But having an art space is a political act, even if you don't think it is. Just like most aspects of life have some political dynamic to them. You have to reckon with those politics while you're making the art.

When you look at the space of BALM or the website, you see a very clear embrace of the absurd and the irreal. For example, on the website, it says that BALM is a continuation of the work of “time traveling representatives of the communist resurrection cult.” How much of this is tongue-in-cheek? And how much of it is sincere? And I know that there's a blurred line there when we're talking about art. But also, why does the weird, the eldritch, the surreal, the irreal suit what BALM is trying to do and the current state of working people's lives?

Adam: I think the answer is yes, and especially yes. It's tongue-in-cheek and real. And partly this is a gesture against a particular version of Enlightenment thinking, that everything has to be rational indeed. I'm not against rationality or science. But I think that there's something limiting about approaching culture in a way that sees everything as whether it's true or false.

What we love about novels and movies is that, at their best, they’re true lies. Throughout a lot of societies, you would perform certain things and you would both be the thing and but not be the thing at the same time. Contradiction could exist. In a performance, a liturgy, a ritual, an artwork. I think that that's true here as well. How much is tongue-in-cheek and how much is real partly depends on future generations.

Like in a million years, if socialism finally happened, who knows what we could figure out? You know, I have no idea. But that's part of cutting against the stultification of imagination in capitalism, I think. Why not? I mean, why not image that society could eventually conquer death? Now, obviously, I wouldn't base what I'm going to do next week at the protest based on that. But we've been so narrowed by possibilities.

I also think that the absurd is also related to the to the concept of gothic futurism that shows up in Afrosurrealism and hip-hop and other cultural movements. We experience ourselves already displaced in time right by capitalism. I always give the example of somebody looking at their smartphone next to the ruins of the River Rouge factory in Detroit. There's lots of other examples in everyday life. Their version of time throws us backwards, but presents us an abstracted view of the future that we don't have access to. What if we could imagine having access to the future and then putting ourselves back into it?

Tish: Yeah we see a version of this in stories about time travel. I think of Ray Bradbury’s “A Sound of Thunder,” where the guy goes back in time, steps on a butterfly, he comes back and it’s fascism, right? The thing is, we didn't need to go back in time to get fascism.

It makes sense to me that people that would constantly tell you not to go back in time and change things would be the people who are on top. They don't want anything changed. I’ve struggled so much under the idea that there was no alternative and the crushing of the imagination. So one of the things that was the most liberating to me that I want to give to other people, and especially that I find myself always trying to give to my students is the question “are you sure that's all there is?” You know, what if there is more? Why wouldn't you want to push yourself constantly to imagine more for yourself and for all of us? I guess my response to the question would be, “I believe in the multiverse.” So yes, it is literally possible.

Just to re-broaden the scope a little bit, I’d like to ask how this original iteration of BALM existed while you two were living Las Vegas. This is a very different location. Some might say Vegas’ perpetual state of synthetic newness stands in contrast to the kind of deep time that animates Southern Illinois, and you already mentioned the challenges of BALM in Las Vegas. Could you say a little bit more about that? How do you think that change in location shaped what BALM does both in terms of art and labor?

Tish: To me, I guess the big difference that I can think of between Las Vegas and Carbondale is that Las Vegas, I mean, it does have a labor struggle history. It has a union history, a history of strikes. So, but you're right that there is, that the time is different, right? So I mentioned immediacy, there's an immediacy of need and immediacy of like struggle in Vegas that doesn't necessarily happen here. Like there's not as much of the connection to the history, I didn't necessarily feel that.

So BALM did some of the same things, but it just felt like the response was different. It felt like what it was giving to people was different. It felt like the experience people had in it was different versus here. Whereas here… you mentioned deep time, right? This is an old place with a longer history that it's way more connected to because it doesn't have so much of the same immediacy and moving parts. So there's just like a, I don't know, a depth to BALM that there wasn't necessarily in Vegas. And I don't know that that's necessarily a bad thing that it wasn't in Vegas. I just think that I like it more having that depth and that deep connection, but it, I wouldn't say that there was no value or that it wasn't as good. It was just doing a very different thing, and one of them maybe I prefer to be doing or prefer over the other.

Adam: Well, I think that when we started BALM in Las Vegas, we had our first event at BALM in our basically large studio off of Industrials Road, which is also Sammy Davis Jr. Drive, next to the Hard Hat Lounge, where we would drink near Naked City. We opened in the fall of 2019, so only a few months before the pandemic started, and we only had a couple of events, and those were mostly meetings of the Agit-Prop Subcommittee for Las Vegas Democratic Socialists of America, was was actually a fairly successful project in a fairly successful chapter.

We only got to do a couple of events. We didn't really get to see what it would look like or get a sense of the dialectic between the community and the space that potentially could develop. But what's different is there's a sense of deep time here, and also a sense of economic and social decline. Carbondale was named that because it was where they loaded the coal mined nearby. Mining towns, factory towns, not a lot of farming. But there is also a university in this town, but a university that historically served working class people.

Anyway, it's complicated, but it's on the decline, and it fits into the same sort of pattern of much of the Rust Belt and Midwest. Whereas Vegas is very much defined, or has been defined, by this other contradiction between the pliable moving symbolism or signification of Vegas. Jean Baudrillard would describe it as sort of a simulacrum of a place, simulation of a place. But also it's the city that Mike Davis described in the book he edited on Las Vegas. He talks about the neighborhood we used to live in, Naked City, which was historically the neighborhood where downtown meets the strip, where the non-union workers and the strip performers lived. Historically, it was called Naked City because that's where the showgirls lived. They’d sunbathe naked outside of their bungalows. And we lived in, well, sort of a quasi-bungalow type building. And Vegas has this weird feeling, because the unemployment rate's actually fairly high, between 6% and 8%, even when times are good. But times are usually good because of the nature of the industry there and how well paying the union jobs are because of the strikes of the Culinary Workers Union. And you have a feeling of pride that prevailed in certain industrial towns a hundred years ago during boom times, where you can show up with a high school education or less. And if you're lucky enough, you can make a really good living. It reminded me of like my parents' hometown in some ways before the factory closed: lots of shops and things for working class people when you get out of the tourist areas. So there is a sense of solidarity and some sense of history here and there.

Now, one of the big concerns we had, like I said, was the gentrification issue because our studio was in an area that was targeted for gentrification and we didn't want to contribute to that. Not because we thought we could stop it, because that's not the case. It would take social movements and changes of policy and so on to stop it. But because it feeds into the meaning of the work itself, right? You can't make anti-capitalist work that's objectively helping gentrification, right? I'm not a moralist but you can't consciously do that and have the work mean what you want it to. We knew we could connect that work up with the social movement here.

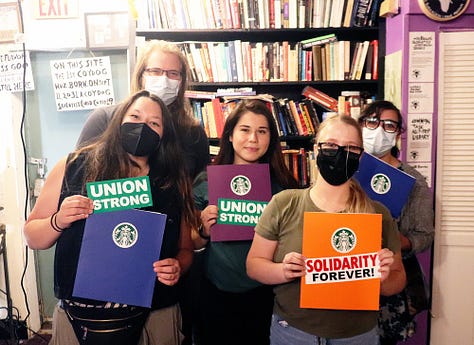

We've had folks from the Starbucks Workers Union meet at our art space. Which was great because we’re really close to the Starbucks location and they could have meetings here and not get spied on by management. We’ve had meetings about defending the abortion clinic here at BALM. We've had fundraisers for No Cop Academy, things around immigrant rights, study groups with the DSA chapter, the YDSA chapter. So we've been able to practically use the space in a way that helps out in some way the actual social movement, but then also hopefully feeds back into the meaning of the work we're trying to do. And hopefully some of the people who use the space for these community and political labor ends get some meaning out of it. Now, I think that could have happened in Las Vegas too. But the way it would have happened would have been different. We'd have to think through really hard things like, should we keep the studio in the area of the city that's gentrifying or not? Should we move it? Should we move the art space somewhere else? Could we afford to do that?

That's another thing. We could afford to do it here. We ended up moving the space into a mid-century ranch house and we live behind it in a bungalow. I will say this Vegas is a weird place in other ways too. Obviously there's a long history of segregation in Vegas and still is informal segregation and racism in a big way. Although it's a very multiracial city and in some ways more integrated than most cities around the country, including New York and San Francisco. One of the good and bad things about Las Vegas is that it's about money, right? So there's very little ideological bullshit in everyday life. Everybody knows everybody's about money. The bad part of that is, is it breeds a sense of we're all fighting each other. On the other sense, it makes things very clear about where you stand, right? I used to love Vegas, I'll be honest. I hated it and I loved it.

So it sounds like the Born Again Labor Museum in Vegas took on somewhat different concerns than it does in Southern Illinois, specific to the local region. Do you think BALM would look different if it were established in, say, Boone, North Carolina, or Fontana, California?

Adam: I'd say it depends on the specificity. I know a little bit about Boone. I don't know anything really about Fontana, California. I think there are cities where BALM wouldn't work, like Santa Barbara. I don't think you could start a left-wing art space that made sense in Santa Barbara. Or, you know, other ridiculously wealthy places. Carmel, California. Or Highland Park outside Chicago. But I think it depends on the specifics because the work needs to connect specifically with the people and the history and the sense of place in those communities. So we made work when we were in Vegas quite a bit. Tish wrote a lot of poems and stories about their experience working at the gas station, near the convention center.

I responded a lot, particularly when I started doing agitprop stuff for Las Vegas DSA. I did a piece that was a slot machine with fists instead of the usual lemons and cherries on it. And it said “individual solutions limited.” So responding a lot to that. And you can think through the cultural implications of the local political economy, and how that relates to what you're trying to say politically and artistically. So you start to think through what are the cultural implications of the political economy and the history.

Here it was mining, right? And some factory work. That's all gone. So there's a sense of a lost past and a lost future that sort of permeates everything. The two largest employers now in our town are the university, which used to employ over 10,000 people. Now it's slightly less than 7,000. And the health system, which employs about 7,000 people. So you have half the town employed in educating and half the town employed in keeping the previous generation alive a little bit longer, a generation that had a higher percentage of union pensions, had a higher percentage of being able to probably buy their own house and things like that, but are slowly dying off. And both are very precarious. The wages at the university now for staff jobs, starting jobs for really hard staff positions where you're coordinating things in an apartment are about $14 to $15 an hour, which is less than you can get working at Taco Bell here. They laid off over 1,000 people at the hospital, almost all the support staff, partly because of the usual administrative crap, but also because they tried to do some of the right things during the pandemic It's complicated.

So you have a sense of less and less all the time. Less future, less past at every moment. So reasserting the future and the past becomes a very political act. So I was much more interested, for example, in the question of gambling. Gambling with your life and future when I was in Las Vegas. Not literally necessarily, but the sense of being in a casino of capitalism. Where now it's more of a sense of lost time. that I've been thinking about more and more. So I've focused more and more on the “Born Again Labor Tracts.” And the content of that has changed too. The first one we did was about a guy named Billy who went to business school because he didn't want to be like his working-class parents. It doesn’t go well for him.

Could you explain a little bit more about the concept behind the “Born Again Labor Tracts” and then go into some of the specific stories?

Adam: I assume you're familiar with Bible tracts, yeah? These unhinged Christian fundamentalist morality tales printed in small comic form. Like, “I had premarital sex and I saw the Devil.” Or, my favorite was this group used to hand them out at our high school, and they had one that headline was “Dinosaurs: a conspiracy between scientists and the Devil!” There'd be these cartoons where like, you know, people were becoming evil and seeing demons or “God's not cool, man. I'm going to smoke a joint, be groovy.” And then, you know, they'd go to Hell.

So we’d do some of those drawings and digital collage, and then we would print them out and collage them onto wood or canvas and press them on the paper. The very first one we did was this guy, Billy, goes to business school. This is something I saw all the time in Vegas. He goes to business school because he doesn't want to be like his working class parents. He doesn't want to be a sucker. But only job he can get is managing McDonald's afterwards because there are no jobs for him. And he gets really bitter and angry and becomes a reactionary. Then the Angel of History shows up and tells him he's an asshole. You know, like, instead of a demon or Jesus or something.

So that was still focused on a sense of gambling with your future, but then more focused lately on the sense of not having. So you might as well do, in the sense of proletarian morality, do the right thing because you don't have a future. You might as well be in solidarity. You might as well stand up to genocide. It's not like you're going to get a fucking job anyway.

Tish: Yeah. When I was in Vegas, and I was at the gas station, I was writing about the homeless people that would come in. And, and, you know, I would see them either at work or walking home from work. Also, this sick wealth disparity of the people who would come in in their sports cars and yell at me because our cappuccino was powdered. How dare we not have real cappuccino at the fucking Shell station on the corner?

So I was writing and responding to the incredible disparity and what it is to live in Vegas, which is just a completely different experience. And then we came back here and I got a different job and the whole tone of the town is different. The whole tone of what is bothering people, what is eating at people, what the consistent issues that people have are different. I mean there are homeless people here but it's, you know, it's a different experience for them. You don't interact with them as much teaching at a university as you do working at a gas station.

What I have written a little bit about recently is that, last semester, I had eight students lose someone to gun violence. They were very forthcoming with me about it. I know that what's behind their experience with that loss is the same economic disparity that's driving people in Vegas. I would see people who were on the street who would come in with their checks every month and gamble them entirely away, because of that chance of having some sort of sudden miracle that get them off the streets. It's a different response to it, so my response was different to it.

And this was what became “The Toilet Key Anthology,” yes?

Tish: Right, yeah. Yeah. Being the person in the gas station who is in control of whether or not someone who sleeps on the street gets to pee and wash their face like that every night is a punch in the gut because you're constantly being told by the people training you and by your management that you don't have to let them, you don't really want to clean up after them. They're dirty. Why would you want them in? Is that the kind of company you want? It was responding to that dehumanization.

So bringing it back to Southern Illinois, you've laid out a pretty clear approach to you know art labor working-class life how does it how does this inform the types of art that balm exhibits here in southern Illinois and the types of events it hosts?

Tish: I think the thing that I am the most proud of, the thing that I tell people about consistently is what we did for the Starbucks workers. And I know that we've done a lot here and the space has been used a lot, but helping that group of people have a space where they could go and safely discuss unionizing their store. I am so immensely proud of us for having been able to give that to them.

In terms of art, and what BALM does. I really, really love the Born Again Labor Tracts so much that I demanded we keep one of the last ones, and it hangs in the bedroom so that I can see it every night when I go to bed.

Adam: We also do interventions into the town. So for the Communist Manifesto Distribution Project, we made yard signs, where you could call a 1-800 number that Tish set up. and order a Communist Manifesto. It was inspired by all the signs around town in Spanish and English where you could order a Bible for free. And we thought it would be funny to put up signs everywhere saying you can get The Communist Manifesto for free. The serious part of that being that this is an entirely legitimate thing. It's just as legitimate as this Bible thing is. And just as existentially important to your actual everyday life to organize and demand your fair share of your life.

We also created these irrealist historical markers, which we call the Big Muddy Monster Atlas Project. The Big Muddy Monster is the local Bigfoot. Really funny story, actually. It was just some guy in a Bigfoot mask who was terrorizing teenagers in the late 60s in Murfreesboro by the Big Muddy River that flows into the Mississippi about 50 miles from there. But it became a local legend. There's a statue of him, of the monster now, next to a McDonald's in Roseboro.

But they're mostly irrealist stories, and they're based, for the most part, on things Tish has written in her work and other stories we’ve published in Locust Review. So we had one sign that says “My body lives here. I live somewhere else,” like R. Faze’s story series in Locust. We put it outside a house on this one side street for this woman who has crazy shit in her yard and she left it up for a week. She liked it! We've done the one about “Dave, from Planet Cleveland who led the uprising.”

These are just metal signs, like metal street signs that we go and put up, you know, not entirely legally. Outside of an abandoned fast food restaurant, we put up a sign saying “This is the future location of Immortality Beaver,” basically a sculpture of a beaver at a fast food drive-thru that gives you immortality, from a story that Tish wrote. Those signs have been really wonderful.

Tish: I took part in something recently called the Young Writers Conference at Southern Illinois University. I gave a presentation where I taught teenagers about critical irrealism. They really loved it and responded to it. And then I also took part in another presentation where we talked about micro-fictions and flash fictions, where I brought up how, if you're a writer, your fiction, your micro fictions, your sentence fiction, doesn't have to just live on a page or on a website. You could do like what we have done and put up signs. One of the things that I really love about those signs is that it’s jarring people back into reality to remind them that this public space is all of ours, you know? So, they could do the same thing if they wanted to, and indeed should.

And I'm not trying to, as I told the teenagers, encourage graffiti, but public space is a communal space. It is our space. I think that you should be allowed to put something up in it, and intervening in that way really makes me happy. Because I feel like I've seen enough of a response from the people in the town, how much it's lit people up. People have stolen the signs and taken them home and put them up in their bedroom, which I fully support. Obviously, I want it to be out in the world, but I love that people saw it and connected with it and thought, “I've got to have that on my bedroom wall or my living room wall” or something. That's been such a really wonderful... way of us putting up art and reaching people and then just grabbing it and being excited by it.

Adam: There's a thing that Joseph Beuys said about Marcel Duchamp. Marcel Duchamp famously put the urinal in an art show at the Armory Show in New York in 1917, if I remember right. He wrote “R. Mutt” on it. It was just a pre-made thing. And Beuys, the post-war German artist, said, the problem with Duchamp is he invented a language and they never used it to say anything. So he used ready-mades, but then he didn't articulate a story with them. And then Beuys tried to do that in his own way. For good or bad, there's good criticisms to make and bad criticisms to make. So the sign thing is something artists were doing. Jenny Holzer, in particular, was doing it in the 80s. But then it was like, “oh, that's Jenny Holzer's thing.” So nobody really has done it again. And this is that fetish of everything has to be new. We're just very subtly different.

So we're not doing what Jenny Holzer did. Hers were all aphorisms like “power concedes nothing” and stuff like that. Ours are stories, which is different. But it's a similar thing with some of the assemblages or the other things we do, the installation and painting work we do. We're trying to steal from and build on these things without thinking everything has to be sprung out fully formed.

The other thing we want to do with the space is to work in conversation with the people using the space: community members labor folks, leftists, whoever we can be in solidarity with, you know, given our situation and their situation and what's happening in the world. But we also want the work to all be in conversation with the other works too, which is probably an argument against this idea that the art gallery has to be this white cube where everything is pinned to the wall like dead butterflies, abstracted from a sense of relationships with other people and other things. So, we put up signs all over town. We also got copies of not all of them, but some of them and put them on the front of our house. So like when you go to our house, it says, “This is where Immortality Beaver lived.”

With the Communist Manifesto Project, tell me a little bit more about that. I think you've laid out really well how and why you did that and what it's riffing off of, what it's seeking to detourne. But what's the response been like to that? Because there's... there was any doubt about where balm stands in any of this you know free communist manifesto signs very much erased that doubt.

Tish: We've only actually had one negative call, and it was just some frat boy douchebag when we put one up on campus. He was just like, “fuck you,” you know, and then hung up, right? For the most part it’s been a diverse range of people from the area who are just like, “yeah, I'm really interested in a manifesto,” or, “BALM looks awesome. Please send it to this address.” We haven't gotten like a ton. I mean, not necessarily. About a dozen. Yeah, about a dozen. I really wanted to get like 25, 50.

Adam: We get calls from all over the country and people have seen it on social media. We can't really afford to send copies to everybody in the country, right? So you do have to live in the area. I thought we were going to get way more of a pushback. It just sort of became like a normal thing. And I thought that it would really offend people seeing, you know, the people who send you the Communist Manifesto. So I was sort of surprised, but it's been really wonderful, actually, the response.

The signs do get torn down really fast. We've gone in several rounds where we put them up around places. They get torn down pretty quickly by, I assume, ideological right-wingers. But most people think it's funny, right? Because it's trolling. We're trolling the people who don't like it. And remember, this is the one county in all of Illinois that voted for McGovern in 72. This is kind of like the Austin, Texas of Southern Illinois – Austin 20 or 30 years ago, not now, when it's a reactionary cesspool of fascist weirdos. No offense to people who live there, but it's not what it was when Slacker came out. This is a pretty interesting space as far as towns go. It's kind of heterotopic. So there's lots of people in town who are totally cool with it. You get 20 miles outside of town, it might be very different. But even there, there's really interesting people around Southern Illinois.

Now, there's also a lot of reactionaries that are very scary, especially if you go toward Marion and some of the other areas. There's also a lot of poverty in the river towns, because Southern Illinois was settled before the rest of Illinois. Those towns are all economically depressed now, even more so than they were 30, 40 years ago. They were already having hard times then. Of course, there's the civil rights fight in Cairo, Illinois, and the white flight that destroyed that city and stuff like that.

Everything is contested, but there are a lot of cultural and political variables that can go the other way in the right circumstances. And I think part of the motivation of the Communist Manifesto Distribution Project, beyond us being trolls and thinking it was funny, was that it's kind of this reassertion of imagination again, a counter-imaginary. It doesn't have to be this way. I had an art teacher when I was a kid. Her grandfather had been in the Communist Party in Southern Illinois in the 30s. And after the war, he became a born-again, conservative, evangelical Christian. Because that's just what happened, right? He went from being a militant around a mining town to, “Okay, it's the post-war boom. Everybody's going to church. I guess I'll be a Christian now.” Over time, that happened. It makes you go the other way. There's no reason it can't go the other way too.

One of the things that stands out to me about BALM is that your favorite projects aren’t confined to the physical space of the Born Again Labor Museum. They seek to very much go beyond those boundaries. And some people might compare BALM to more mainstream, well-known museums and be kind of confused by it: the curation, the engagement with socialist politics, the community involvement.

We're very used to seeing museums stand apart from the surrounding communities, but as you said, that's a stand-in for some very nefarious economic relationships. It’s not just with gentrification but, for example, the relationship that the Guggenheim has to BP oil. It seems like BALM mostly, or one of the big things that motivates it is sort of trying to redefine where and what the museum is, the role of art and how we interact with it in daily life. What do you think are the prospects for a different model like that of BALM to thrive and flourish? Are there others like you out there? You know, what, what, What are the prospects here?

Tish: I don't personally know if there are others out there. I would really love for there to be. I think if people wanted to do BALM-like things in places that they really could. I am originally from central Illinois, and it is a dead factory town. It is politically very right-wing. Even the most liberal people there are probably going to be some form of deeply problematic or bigoted. You know, they're going to have some kind of backwards idea, even if they're trying to come from a place of not having that. So it might be really difficult because of the way that that sort of social structure might constrain. But it also might provide more opportunities. And it might actually be something that people would hunger for more.

So I actually think that even if it was more of a challenge, it would make it more worth it. And it would probably make it stick a little harder or have a better response. Not that we haven't had a good response here. Maybe a better response than you might assume. So anyone that would want to do something like BALM, I think they should.

Adam: There's other artists doing similar kinds of artworks as us, but not necessarily in a sited space. I think the prospects depends on the prospects for the working class on the left in a lot of ways. We've seen the prospects of left ideas and leftist art go up and down with the prospects of the working class and the left. There's an audience for this stuff, a constituency and a community for this stuff. When there's an audience, a constituency, and a politics of emancipation.

I think the other aspect of it is art museums in general, mainstream art museums, are in a crisis or a series of crises of the historic ideology that justified art, bourgeois high art, quote unquote. The idea of art for art's sake was jettisoned in the late 20th century in favor of other ideas like postmodernism and poststructuralism. And so the art space lost some of its raison d'etre. But now art faces the additional problem of substitution. Ben Davis talks about this in his recent book on art. A substitutability crisis, similar to what theater faced with film and what film faced with television. Are people really going to go spend, I mean, people do, but how many people are going to go spend hours contemplating one painting or a few paintings where they can scroll images endlessly on their phone?

So there's a sense of crisis about what the art space should be because of this philosophic change and this technological cultural change that feeds things like relational aesthetics or the idea of the art space to be an “experience.” This is related to what Claire Bishop talks about as normative attention. There is a normative sense of what attention should or shouldn't be. When people complain about people being distracted by their phones, they have an unspoken normative sense of what people should be paying attention to. Now, there's things to criticize about social media, as well as the historic contemplation of the art object, but those need to be rooted in the actual material and ideological functions of those things.

Contemplation of the art object traditionally had good aspects, but it was also related to this sense of aggrandizing the bourgeois individual, the idea of individual genius, the separation of the art object from context. Whereas the way attention works on social media is about mapping our subconscious, turning that into information that can be commodified and so on. So they're both products of capitalism at different points and in different different ways, and I think that one of the ways to correct this is not to necessarily reject the digital space, because we have to live in this world, but also not necessarily to reject it in real life space, but maybe refocus what our attitude is to both.

Is our audience the “art world”? Maybe sometimes, but it doesn't have to be. It's one of the reasons I look at outsider artists a lot. I think that category is very problematic. It flattens the work. But one of the things I really like about the work is it’s almost always oriented on a broader audience or an audience outside the art world. You can make art for people who aren't part of the art world. The weak avant-garde, because it's afraid of strong images and strong politics, can't save itself. It has to be saved by things that come from outside of itself.

All photos courtesy of the Born Again Labor Museum unless otherwise noted.