Salvation

An execution story.

Chag Purim Sameach. In the spirit of the carnivalesque and Talmudic reinterpretation, I offer a short postscript to the typical Purim spiel. Enjoy. And please do subscribe…

“It may indeed be the highest secret of monarchical government and utterly essential to it, to keep men deceived, and to disguise the fear that sways them with the specious name of religion, so that they will fight for their servitude as if they were fighting for their own deliverance, and will not think it humiliating but supremely glorious to spill their blood and sacrifice their lives for the glorification of a single man.” – Baruch Spinoza, Tractatus Theologico-Politicus

The rope was very coarse. Haman could see it would chafe and burn on his neck. He wondered if it had been woven from the same thorny trees they had cut to build the gallows. It would have made for nice symmetry, but he was quick to put it out of his mind. Rope made from vines and plant fibers was notoriously weak, completely unsuited for hangings.

Besides, he presently had more important matters to think about. Today was the day that he, King Xerxes’ chief minister, his most trusted advisor, would be executed on the King’s own orders.

Strange… the gallows he’d ordered constructed outside his home had, of course, not been for him. Yet it was he who would hang first from its towering top. It was a magnificent gallows, awe-inspiring. He stared up at it, squinting his eyes against the noon sun, and recalled his order to his slaves to carve it from the tallest camelthorn in Susa, fifty cubits high. They had done their job, he had to admit. Stretching above Haman’s sprawling gardens, the orchards of apple and pomegranate, it seemed out of place yet entirely correct.

The plan had been to watch from the Citadel, at the King’s side. To show Xerxes how he would always be the King’s unwavering protector. Some had thought the young King feckless and mercurial, easily swayed. Haman had always sneered at these whispers, thought them close to treason. It did not matter what the King’s personality was. What mattered was that he was the King.

It was as true for Xerxes as it had been for his father, the revered Darius. Darius had expanded the empire, encompassing more cities and tongues than ever before. He had built Susa and Persepolis, had rebuilt Babylon into a towering metropole. That was Darius’ lot in life, just as it was Xerxes’ lot to rule it in his father’s steps, and for Haman to serve Xerxes. Those who thought otherwise, who found reasons to refuse their lot, to refuse to serve and bow, deserved nothing but scorn.

Susa was swarming with these kinds, the traitors and opportunists. It was a fair price for the greatness of rule and conquest. But it meant that it was only a matter of time until one of them tried to get close to the King. That it was Mordecai who gave Haman the chance to demonstrate this to Xerxes was, he thought, proof that he was the most righteous minister a King could deserve. Mordecai, of all the smug and duplicitous Hebrews in the empire. Mordecai, who all those years before had given Haman food and, in return, had hung a humiliating debt of slavery over Haman’s head. It was too perfect.

As for Haman’s idea, intimated to the King, that it should not be the empire’s military who eliminated the Hebrews, but the people of Susa themselves… this was a stroke of genius, one Haman was still proud of. Not only would Susa be finally rid of a treacherous people, but the city’s populace – be they Greek, Phoenician, Arab or Ethiopian – would be given an enemy. The kind of enemy that ensures a King’s rule as protector in the eyes of his people.

And to make it all that much sweeter, Haman would watch, alongside King Xerxes, as Mordecai swung and twisted and jerked above his own estate. A sign to Xerxes that he, Haman, and everything he owned, would be in service and protection of the King.

Had he known about Esther… well, that would have called for different calculations. One of Mordecai’s kind had indeed gotten close to the King. It was Mordecai’s niece no less, and she had wormed her way so far into Xerxes’ graces that he had made her his wife. They had made a fool of Haman, that was for sure. At the very least, he would die without having ever been Mordecai’s slave.

He felt movement across the courtyard and let his eyes be drawn from the gallows. Esther and her retinue – three bodyguards, an advisor, and, curiously, a court scribe – stood just outside the doorway. It was her home, according to the King. His position in court was now held by Mordecai. The gallows, and the rope, were for Haman. He might have marveled at it had he not spent days in his cell cursing them both, his hatred for them and their people seething in his gut. Though his mouth was dry, he spit on the ground before her.

Beyond the walls, between his estate and the Citadel, the city of Susa tore itself apart. Haman had kept his gaze fixed downward during the journey from the Citadel to his estate, did his best to ignore the screams and cries, the echo of iron and stone clashing. Xerxes had decreed the Hebrews could fight back. What was supposed to be a cleansing was now merely a bloodbath. In the days to come, the fighting would subside. Or perhaps it wouldn’t. The Gods knew what lay ahead for Xerxes now.

He felt the noose tighten round his neck. As he had suspected, it scratched and itched. The rope dangled from the nape of his neck, and he watched as it snaked upward, fifty cubits high, then back down again where four hulking soldiers were taking it in their hands.

These were the last moments. It was a small audience: a sparse detachment of soldiers, Esther, and her entourage. Not even Mordecai was present. Not even the King. Everyone stood stock still. The sounds of battle on the other side of the estate walls was far away, faint. The only movement Haman could make out was the quick scribble of the scribe’s quill against the roll of parchment.

He caught the look of the soldiers’ commander. His brow was furrowed expectantly. That’s when Haman realized he was being allowed the small dignity of final words. “I have been proud to serve the King,” Haman said. His voice was cracked and reedy. “I make no apologies for my loyalty.” Then, briefly, looking at Esther, “or my hatred.”

It would be a long way up to the top of the gallows. He reckoned he would feel all of it: his breath squeezed out his lungs, his windpipe crumpling in his throat. He would feel the blood vessels pop, the muscles in his shoulders and neck and face writhing and twisting. All before his neck snapped.

It was guaranteed to be an agonizing, excruciating end. Still, he didn’t wish for a quick death. He hoped, prayed, to stay awake as long as he could, until he reached the top of the gallows. So he could look, one last time, at the Citadel. King Xerxes would be watching. Maybe Haman would catch his eye. If so, then the King would know that, whatever his other mistakes and missteps, he had never once, not for a moment, been disloyal. Xerxes would never find a better servant.

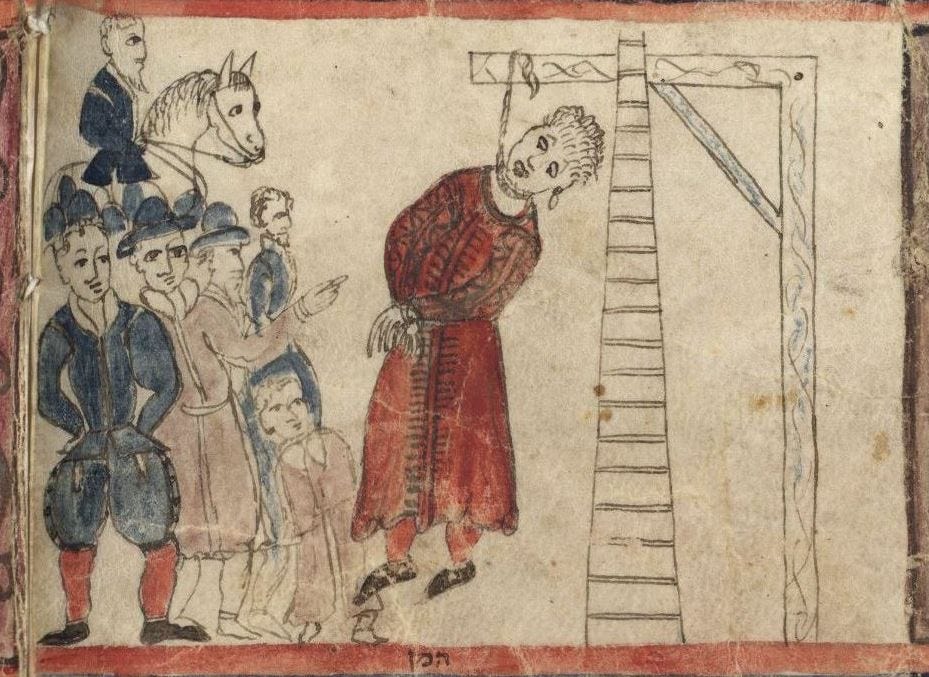

Header image is a detail from the Megillat Esther, Moshe ben Avraham Pescarol (1617).