That Ever-present Hum

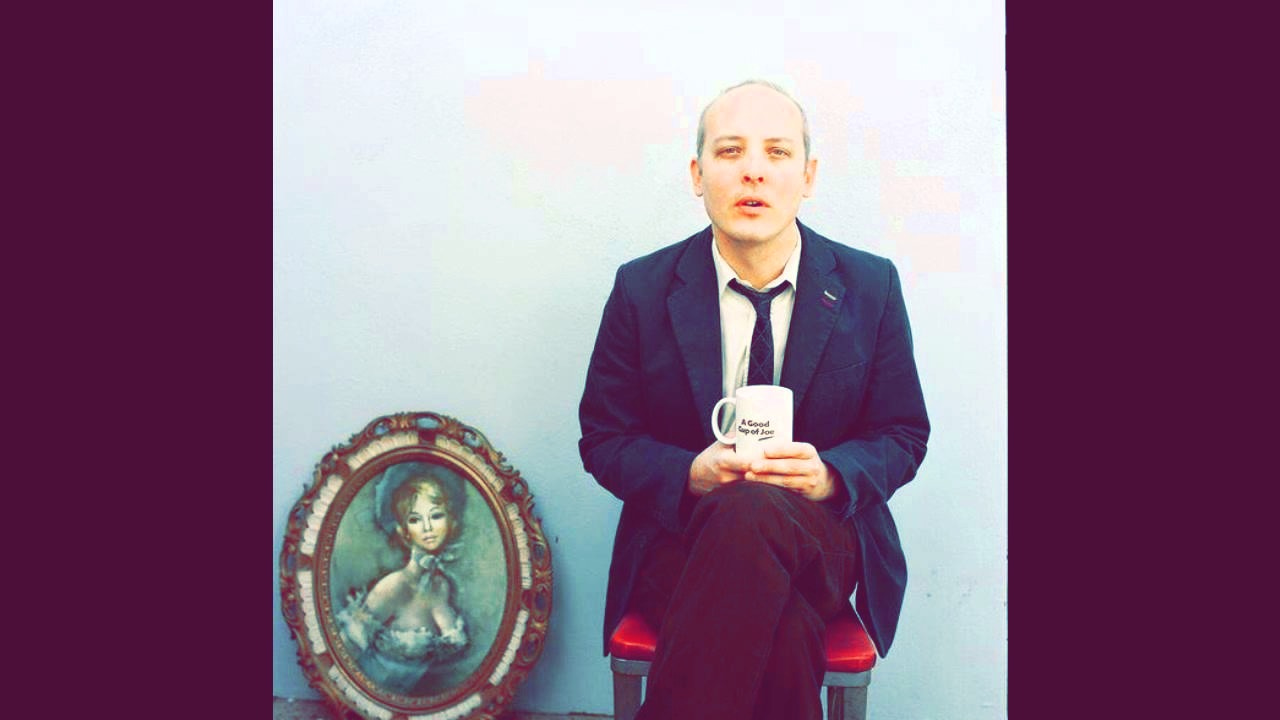

On the work of Brian McBride.

Appearing on Steve Molter’s Five Questions podcast in 2017, Brian McBride refused to rank himself. When asked what his greatest accomplishment as a musician was, he was not so much stumped as on a different wavelength entirely. When pressed, he responded.

Just providing an anchor or a ballast through hard times. These times are fucking hard. They're fucking hard no matter what it is that you do. And so the littlest things are of extreme importance. To think that I could be one of those little things is great.

McBride died in the final days of August. So I’ll be forthright. Not only was McBride correct about this weightiness, about the ballast of detail, but his music rather helped show it to me. Depression operates in a peculiar way; one of the reasons its sufferers describe it as far more than mere persistent sadness. The glooms are all made of thoughts and moments that take on a heft far larger than their actual size.

By the time I first heard Stars of the Lid – the ambient music pioneers of which McBride was one half along with longtime friend and collaborator Adam Wiltzie – I was drowning in these unbearably light thoughts. I had raised myself on the heavier genres: punk rock and the darker iterations of “post-punk,” metal, the noisier sides of hip-hop, the first wave of American “indie” that took their cue from the likes of Husker Du and Black Flag. Their anger had sustained me through so many collapses, both socio-political and personal. The older I got, the less they served that function.

I was, in many ways, the perfect audience for what Simon Reynolds described in his piece for The Wire back in 1995, even if I only came to the article – and the music celebrated in it – fifteen years too late. “Rockism” (should we need a term for the aesthetic expectations that followed in punk, indie, low-fi, etc.) had become a spent force, unable to fully articulate the structure of turn-of-the-millennium feeling. Groups like Stars of the Lid (named for the light artifacts that float through our vision when we close our eyes), Labradford, Tortoise, Sabalon Glitz and others were discarding these trappings and finding new ways to give expression to the ambiguity, shape to the frustratingly shapeless.

A quick summation of this article, as read by DJ John Peel, would later be unselfconsciously sampled into Stars of the Lid’s “J.P.R.I.P.,” their 2007 tribute to the late legendary radio DJ. As if to endorse Reynolds’ and Peel’s respective understanding of what the group was doing.

The best iterations of “ambient music” (again, a static term used to discuss an ever-shifting set of aesthetic markers) give weight to the ephemeral. Not for nothing did Brian Eno start his career as a key part of Roxy Music, an act that personified glam rock’s campy-poetic celebration of the discarded and tarnished. (Reynolds also spends a good amount of space in his brilliant Rip It Up and Start Again examining Eno’s earliest ambient experiments and their own relationship to the first wave of post-punk. One gets the sense that, while the mainstream will always be searching for music that can be pitched at “just the right volume,” the artists that really matter will be more aware of the dialectic between extremes: cacophony and quiet, chaos and stillness.)

By the time it was McBride’s and Stars of the Lid’s turn, there was arguably a lot more detritus to choose from, more ruins to explore and rearrange sonically. You can hear it most distinctly in Stars of the Lid’s first two albums: Music for Nitrous Oxide and Gravitational Pull vs. the Desire for an Aquatic Life. Even in their titles, you can sense the tension between heaviness and ethereality. A nitrous high is on the one hand happy, giddy, euphoric, filled with giggles. On the other, it’s liable to make your extremities go numb, making them difficult to lift or control. You are pulled, as suggested in the title of the second album, between floating and being irresistibly stuck on the ground.

The story goes that McBride and Wiltzie were fond of staying up late, normally getting high on whatever was at hand (normally mushrooms). They’d then dive into the liminal hours of very-early morning television. Infomercials. Public access weirdos. Fringe evangelical preachers. Anyone who has done this, even while sober, knows the feeling instilled by these kinds of programming: where you aren’t sure if you’re actually watching what you’re seeing, or if you’ve finally fallen asleep and are just dreaming it.

Both albums sound like this spacey drift, floating between disparate nodes that might make up something coherent if existence hadn’t lost its center. Long, drawn-out drones, more and more details slowly emerging along the way which, by the time they’ve entered your consciousness, you can no longer remember not being there, before they start to morph into something else entirely. One gets the sense that these albums are attempting to find, or maybe create, some kind of structure out of a complicated nothing.

Stars’ third album, The Ballasted Orchestra, sounds as if the duo has finally found something to tenuously grab onto. The opener “Central Texas” bears a lot of resemblance to the low, sustained drone atmospherics of their first two albums, but seamlessly gives way to a notably different vibe in “Sun Drugs.” Clocking in at over twelve minutes, the song is a swelling, shining vibration, the sound of a gently-plucked guitar occasionally making itself heard, before transitioning into an airy, harmonic string arrangement. It’s entirely likely to have been inspired by the feeling of seeing the sun finally rise after spending all night tripping: the knowledge that you’ve experienced one more step in the cosmic ballet that turns night into day. To us, it feels like a drift, but it’s all part of the universal calculus.

Much of the rest of the album returns, far more pointedly and consciously, to the themes of late night isolation. After the experience of “Sun Drugs” lingers over them, though, along with the knowledge that these kinds of moments are as inevitable as their end. It’s evidenced in track titles like “Fucked Up (3:57 AM)” and the two-part “Music for Twin Peaks Episode #30.” McBride and Wiltzie were both big David Lynch fans, which only makes sense, as does their wish for the original Twin Peaks to go beyond its abrupt end in its 29th episode.

Thinking back on the 21st century’s first decade can often feel like staring at a gap between the late 90s and the 2010s. We now know it to be the gestation of our particular phase in the monoculture, in which mass diversity Taken in full context, so much of what might have been culture during this decade just feels like a very noisy nothing. One gets the sense that there was great art in there, and there most certainly was. The problem was that there started to be so much of it that parsing through it became literally impossible.

Maybe it was because they already had a decade of practice. Or maybe it’s because they already had a grasp on certain musico-cultural threads that prevented them from getting lost. In any case, the aughts were the time when Stars of the Lid came into their own. Their albums from this era – particularly 2001’s The Tired Sounds of Stars of the Lid and 2007’s Stars of the Lid and Their Refinement of the Decline – are absolute masterpieces. There is a more pronounced melancholy here, and in some respects even resignation. But there is an equal measure of renewal. Each album was released either directly after or a few months before the two biggest calamities of the decade for the United States: the September 11th attacks, and the Great Recession. These were moments that fundamentally altered the expectations of what America was going to be in the 21st century, when we first acquainted ourselves with what it means to live not just in an enfeebled, arrogantly sluggish empire, but one that had no sense of responsibility or care for its own internal stability.

Even with one of their members no longer living stateside – Wiltzie moved to Brussels sometime in the late 90s – Stars clearly felt that there was something being lost. While we may be ambivalent about that loss, it nonetheless leaves us even more adrift. Still, we continue, hoping that the lack of certainty might eventually provide as much hope.

I have no doubt that this is what made their music resonate so deeply with me when I first encountered it. I cannot remember exactly when I first heard Refinement, only that I was struck with how much the acoustic instrumentation ended up sounding like an electronically composed soundscape. Flugelhorns, harp, and cello create the same ineffable sonic substance we are used to hearing created through synthesizers and samples.

Listen, for example, to “Even If You’re Never Awake,” a composition whose title alone stirs up some humbling and tragic undertones.

Harmonies swelling into view, seemingly from nowhere, the intermittent hum rising underneath you, lilting piano and plaintive clarinet themes returning with wave upon wave. Now imagine hearing this in the dead of a Chicago winter, snowflakes powdering the sidewalk with the sound of ice floes on Lake Michigan – just a few blocks away – crashing together. Imagine being in your fifth year of unemployment or under-employment, knowing the desperation of the food pantry all-too-well. You can understand how these sounds become cathartic, a reminder that amid so much inertia, gravity still exists.

There is something in the fact that McBride was born and raised in Irving, Texas that goes a long way in explaining much of his solo work. Texas, along with most of the American southwest, is one of the uncanniest regions you will ever encounter. Irving’s inclusion in the state’s largest metropolitan area – the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex – doesn’t really allow you to forget this.

If The Dead Texan – the bluntly-named collaboration between McBride’s erstwhile collaborator Adam Wiltzie and video artist Christina Vantzou – gave articulation to the sparsely-placed people and landmarks that punctuate the region’s open space, then McBride’s When the Detail Lost Its Freedom – released around the same time – sounds like the open space itself. Like The Dead Texan, there are a few human voices found on the album, but unlike Wiltzie’s counterpart, they are mostly unintelligible. As if we can only make out their faint echo, but still hope the emptiness can connect these disparate living dots. There’s a bit more traditional instrumentation here, or certainly more that sounds like it. Piano chords, strings and horns dance in and out of vast and indifferent soundscapes.

But if When the Detail attempts to draw these lonely moments together, 2010’s The Effective Disconnect has us ask if we are in fact witnessing a drift apart, a slow disintegration rather than a coming together. The album’s cover art is a picture of several honeybees, but blurry and out of focus, and the album served as the score to the 2009 documentary Vanishing of the Bees, which is about the growing phenomenon of colony collapse disorder.

As we all well know by now, the future of honeybees is no small component of the Earth’s ecosystem. Pollination makes possible countless essential foods – fruits and vegetables mostly. Without them, large parts of the food chain collapse. “If the bees were to disappear as a species, humans will join them,” writes Richard Seymour. “Some say within four years. We will drop like bees, by the billions, famished.”

If this album sounds like emptiness asserting itself – a process at once tragic, terrifying, and awesomely beautiful – then that is, of course, on purpose. McBride does nothing so prosaic as demand we pay attention to the calamity. Rather, music’s floating resonances, its drawn-out strings and faraway piano, sound more like a requiem for something magnificent that has already been lost. It’s as if the stillness is filling not just space but time, reaching backward to past events as much as outward into the moment, standing in for a quiet-but-devastating future absence.

“Communicating beauty can’t really be forced,” McBride said in an interview with Headphone Commute. “You don’t want it to become merely ornamental or trite. But the main concern was for the music to serve as a reminder as to how fragile this ecosystem is. We all need reminders how fragile the world is around us from time to time.”

Given how much of Brian McBride’s music seems to live in the not-quite tangible, his work with more conventional bands almost comes off as awkward. But here, “conventional” is a relative term. Sure, there are discernable rhythms and riffs in the Pilot Ships’ songs. For all that, they sound more like ambient artists making a rock album, unable to be confined by the limits of the more conventional genre. That There Should Be an Entry Here, an album comprising several three-to-four minute loose folk-rock songs, ends with “Looked Over (No Fun reprise),” speaks volumes. This is a 25-minute track, but the music – mostly sparse guitar and vocals – only lasts for about the first five. After that, it’s a full twenty minutes of almost imperceptible ambience. The sound of wind or faraway traffic, someone quietly getting up from their seat, etcetera. And once again, the low hum that emerges from nowhere.

Musical convention is an equally loose descriptor for Bell Gardens, McBride’s collaboration with the prolific Kenneth James Gibson. What struck me at the time I first heard them was how quickly reviewers seemed to identify Bell Gardens’ music as “psychedelic.” Call it the last vestiges of my musical philistinism, attribute it to the fact that I had yet to fully experience the wonder of psychedelics myself. To me, psychedelic meant something multi-layered, multi-colored, something that could skate between dreams. That wasn’t what I heard in Bell Gardens. In fact I was very much initially turned off by the group due to its undertones of Christian mysticism.

Listen to these songs. They’ve got drums, piano, guitar, bass. Lap steel and Hammond organ. Choral vocals. Gibson and McBride deliberately used only analog instruments to make Bell Gardens’ music. There’s enough delay and reverb in much of it to create basic atmosphere, but I simply didn’t get it. At least not at first. Like everything else with McBride’s music, it’s less about the signifier, more about what it signifies, the feeling in the space between moments.

Bell Gardens is named after a city, albeit a small one, just southeast of Los Angeles. When any of its 40,000 residents tell anyone outside of Los Angeles County where they are from, they are met with blank stares. The Henry Gage Mansion, built in 1795 and the oldest surviving house in LA county, now in dire disrepair, molders away in Bell Gardens.

Why exactly McBride and Gibson decided to name their band after this place isn’t clear. There is a clear influence of Tim Buckley in the music of Bell Gardens, and the town is where Buckley grew up and started playing music. It’s also entirely possible that it was a throwaway suggestion. Given that both musicians were living in LA at the time of the group’s formation, it isn’t difficult to imagine the two driving by a sign for the town, and deciding it was as good a name as any. It feels about as poignantly random as being born in any of the countless interstitial locales whose existence is squeezed between massive metropoles and endless expanses of empty space.

This cosmic randomness is unmistakably present in Bell Gardens’ music. At moments, it seems to lift into the air, almost transcend. Plenty of musical themes drift in and out, though often with more seeming purpose than in Stars of the Lid or in McBride’s solo work. There is also, though less prominently, that same hum we’ve heard elsewhere. But here, it seems to create weightlessness as much as keep matters grounded.

In this context, the vague mysticism manages to be both other-worldly and undeniably terrestrial. Whatever we may or may not think about psychedelia, it is worth noting that the original definitions of the word “psychedelic” emphasized profound knowledge of self over anything having to do with drugs. It was as much an experience of putting one’s feet firmly on the ground as it was letting their head escape into the clouds. As much to do with species being as spirit being.

Brian McBride’s most accessible recordings stop here, with this last Bell Gardens record, in 2014. There were other collaborations and remixes, but none that so prominently featured McBride’s influence. He and Adam Wiltzie had, for a very long time, promised more from Stars of the Lid. More material has been recorded, though, characteristically, they have taken their time finishing and releasing it. Wiltzie once quoted McBride’s reason for this long wait: “You don’t want to manufacture longing.”

Very true. The real thing hurts a lot more, sometimes drives us to the edge of our sanity. It’s also so much more exquisitely human, more able to give voice to that constant droning in the back of our skulls that tells us we could be so much more than we are. Since McBride’s death, Wiltzie has promised to release these songs, though the departure of his dear friend and collaborator will likely further draw out that process. Catharsis, as always, only comes in the longest moments.

In other news, Hangman, the short film I produced alongside my partner Kelsey Goldberg and many others, has continued making the rounds at film festivals around the United States. Most recently, it screened at the Pictures Up! Film Festival in West Hollywood, where it won three of the four awards it was nominated for, including “Best in Fest.” There are more screenings to come, including at the Burbank International Film Festival, Tallgrass Film Festival, Twin Cities Film Fest, and others.