That's Not Me

Music and space in gothic capitalism.

The following was delivered, via Zoom, for the launch of Adam Turl’s book Gothic Capitalism: Evicted from Heaven and Earth, as part of Le Grande Transition conference in Montreal on May 27, 2025.

I will also be delivering a paper at the Historical Materialism conference, to be held London from November 6 - 9. The title of paper is “From Modern Materialism to Popular Modernism: (Re-)constructing a communist methodology of aesthetics. More details forthcoming.

On December 2nd, 2016, during a performance of several electronic and house music artists, the Ghost Ship performance space in Oakland, California caught fire. The Ghost Ship was a warehouse surreptitiously converted into an artist collective.

The building was not built as a performance space. It had neither sprinklers nor sufficient fire extinguishers. The fire spread quickly. Thirty-six attendees, including artists and musicians, died. Blame immediately fell on the artists themselves. After all, legally, they weren’t supposed to be there. But with gentrification and the disappearance of cheap rents making independent performance spaces and even existence as an artist impossible, where else were they to go?

Promises were made to investigate, and indeed, the primary renters of the space went to trial, a few went to jail. But rents for workers and artists, in Oakland and elsewhere, remain increasingly unaffordable. Beyond Oakland, police used the tragedy as a pretext to evict other alternative art spaces.

As if this weren’t enough, the Ghost Ship tragedy also found its way into the sights of the American far-right. Still high from the first election of Donald Trump just a few weeks before, and seeing any deviation from an arbitrary norm of Americanness as another manifestation the queer, woke threat, right-wing message boards lit up with gleeful socialized sadism. Users encouraging each other to search out underground venues like the Ghost Ship, report them to local police, even take matters violently into their own hands.

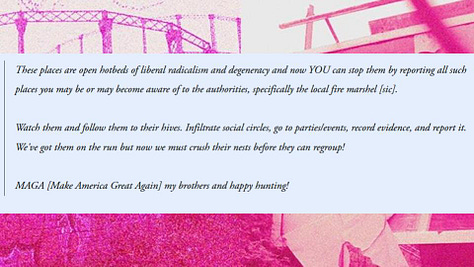

Seven years later, October 7th, 2023. As part of the incursion across the Gazan border into Israel 378 attendees at the Nova trance music festival at Kibbutz Re’im, were killed by Hamas militiamen. The events themselves, and the countless horrific stories, were broadcast around the world, and used as pretext for the full-scale assault on Gaza by Netanyahu’s Israel. As we know, this assault, this genocide, is ongoing.

How can they attack a music festival? observers asked. A naive question. For just five kilometers away is Gaza itself, an area that, well before October 7th endured two decades of siege and blockade. Where Israel monitored and repressed everything from Palestinians’ political activities to their daily caloric intake. Where peaceful protesters who approached the border fence were fired on by the IDF.

How can insurgents think of attacking a music festival? We will be unable to answer this unless we first answer how it is that any festival takes place within earshot of the world’s largest concentration camp.

These are two moments are the coordinates of music’s current spatial exile. Marx observed that capitalism annihilated space with time. Fredric Jameson updated and flipped this on its head, arguing that the architectures of late capitalism annihilate time with space. Both are accurate, pulling our built environment and the individual subject in impossible simultaneous directions, the arrhythmia that Henri Lefebvre diagnosed contemporary urban space with.

Music, with its reliance on rhythm, simultaneity, syncopation, also has a specific relationship to time. These temporal and spatial relations have also been privatized and disrupted. Its fields of experience narrowed by the rise of personal listening devices, headphone culture, streaming services and the algorithm. What has, anthropologically speaking, always been a collective experience has been atomized and disconnected.

In light of this, capitalism makes music’s homogenization all but inevitable, fodder for background noise, designed to soothe our anxious, exploited, traumatized psyches: manufactured by AI-generated ghost artists, piled into playlists we neither have nor want control over. The worker musician, liked the worker artist described by Adam Turl in Gothic Capitalism, is increasingly confronted by a spectacularized cultural landscape, that divorces human creativity and human labor from their temporal and historical valences. The shapes and paces of daily life are often beyond the control of even the richest and most powerful, more the product of late capitalism’s anarchic inertia than anything else. The mass human imagination, in both its individual and collective iterations, is exiled from history.

The scene, the geographic and temporal space of difference that made it possible for artists to live, create, collaborate, and flourish, is strangled. The average price for a home in San Francisco’s former hippie hub of Haight-Ashbury is now $2.3 million. CBGB is replaced with a John Varvatos boutique.

As such, the artist is doubly exiled, not just from history but from themselves. By now it is old hat to say that virtually all art in late capitalism is an attempt to confront a deep alienation. But in confronting that personal alienation, artists also frequently confront their ability or inability to create history. Take the video for Skepta’s 2014 track “That’s Not Me,” in which the grime MC asserts an individuality past the glamorous trappings that often surround hip-hop’s various styles. This was about two years before Skepta won the Mercury Prize, and grime finally came to be considered a valid part of the UK’s musical landscape by the music industry, still when the style’s associations with the housing estates of urban Britain made it the target of police raids and radio censorship.

There’s much to say about the song and the video. What bears mentioning in this context is Skepta’s use of headphones as a microphone. This isn’t exactly novel. It’s a common enough practice among musicians with limited resources. It is very fitting however. Turning an instrument of music’s isolation inside out, using it to project the rhythms and experiences of the artist back into a collective milieu.

It is also a synecdoche for the kinds of musical approaches that will be needed as neoliberalism gives way to what is still taking shape in its place. The commodification of life has emptied time into a linearity of mind-numbing sameness. It has turned public space into a threatening reminder that you exist at someone else’s whim.

Given what we know about the likes of Trump, Modi, Orban, Milei, Meloni, as well as Farage, and the various personalities of France’s Rassemblement National, it is not far-fetched to imagine lived time transformed into a telos of absolute despair. Death, jail, or work. Take your pick. Or to imagine pseudo-public space giving way to expanding sacrifice zones and inverted gulags: undesirables locked out rather than in.

There is, without a doubt, a musical counterpart to this. We have already heard and seen it. Just as artificial intelligence takes the human element out of the annihilation of Gaza, so does it raise the possibility of music made without human input. This is already commonplace. We can turn our noses up to the audio equivalent of slop as much as we want, but the more of it that’s created, the more it homogenizes the means and averages of sonic possibility.

Classical music is already piped into train stations and public squares to deter “the wrong kind of people.” Can noise instantly be tailored to chase off over-surveilled youth, based on a data-mined profile, be far away? Maybe. But maybe not. Every eventual watershed dissolves another layer between the present and the most dismal, dystopian version of the future. We are not ready for it. But we can and must envision the kinds of utopian ruptures that have always been a vital lifeblood of the revolutionary prospect.

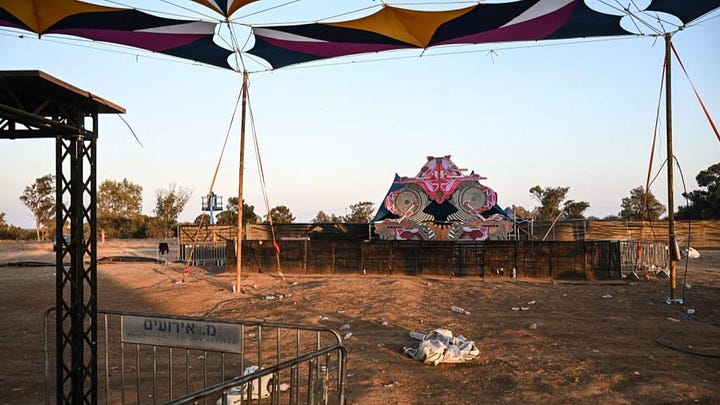

These have been part of our movement since at least the songs and poems of the Diggers in the English Civil War. But it is only with the advent of modernity – and specifically modernism – that the direction of their gesture started to take shape. While modernism dared to dream of the future, its boldest, most radical iterations took what Walter Benjamin called “a tiger’s leap into the past.” Malevich’s blunt squares and crosses referenced and replaced religious peasant ikons that went back centuries.

The delta blues quoted slave spirituals and West African music in such a way that made them fit inside and apart from the railroad economies that unleashed the form into urbanized areas. It also was, notably, celebrated by the surrealists for what it was: a howl of those deemed invisible and disposable. The “blue note” a note that could not be quantified in the confines of western music annotation, became a common reference for the virtual entirely of popular music.

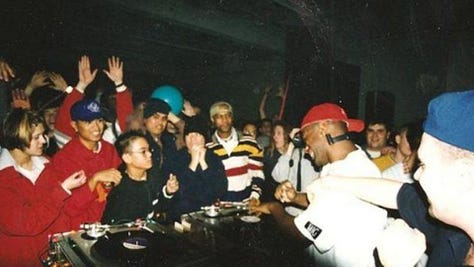

The reclamation of time inevitably requires the reclamation of space, as the rave scenes in Detroit, New York, Chicago, London, Rotterdam and beyond showed. Old warehouses or factories or disused train yards, abandoned by neoliberalism, were transformed into sites of collectivity. When police and governments came for these spaces, they had to politicize to be protected, often quite quickly.

In a moment that threatens absolute wreckage, this gesture of salvage, of radical reinvention of what capital would rather discard and forget, becomes all the more vital. When anachronism insists on its own existence despite the steamroller of official time, it disrupts that time, opening up the potential for a different trajectory. It reclaims the collective-utopian valences of artistic expression.

More recent radical cultural frameworks have attempted to accentuate this. The thrice-dead “salvagepunk” of China Mieville and Evan Calder Williams centers the principle of reinventing out of the discarded. The assertions of the late Mark Fisher’s “popular modernism” sought to discover the democratic nexus between the popular and the avant-garde.

In this respect, the kinds of musical expressions to come will not be unique. They will simply have to be more forceful, clinging ever more fiercely to what has been left behind, reaching even harder into the future. They will have to embrace what, pivoting from Turl’s “weak strong imagery,” we might call weak-strong sound, cobbling together a collective dream that stands in contrast to the nightmares of disaster nationalism. Particularly as the repressive tolerance of neoliberalism gives way to outright repression.

Musicians and artists that did not behave within the parameters of late capitalism’s cultural logic were until recently very easily ignored out of existence or metabolized into a sanitized version of themselves. Now they have to be boycotted and cancelled, gleefully driven out of the center of cultural consciousness, the full weight of political and cultural respectability brought to bear.

Consider the furor around Kneecap, Irish republican rappers from the working-class areas of West Belfast whose decision to rap in Irish Gaelic could have easily been pigeonholed as a novelty by the music industry. Each tiresome controversy around the group has simply gained them more fans, brought their music to the attention of more young people. Their streams have increased. Their shows have sold out quicker. And a few more people know how to say “fuck the cops” in the Irish language. They know how to game the spectacle

To be clear, this is a gothic, salvage approach too. Listeners identify with Kneecap’s lyrics partly because of its references to grime, IDM, the rave scene, and partly because they portray, vividly, young people displaced from time, anachronized, left to the anarchies of history’s backgrounds. Stories of boredom, scapegoating, harassment from cops, random sex, the anxieties of mental health and poverty. The thrills of petty vandalism and doing handfuls of drugs. In other words Kneecap’s music seems to reach toward a postcapitalist desire, an impulse for a mode of being more enjoyable than the present and cobbled together from its detritus.

Their appearance at Coachella, however, in which they projected messages opposing Israel’s war on Gaza, has been countered with calls to have their work visas revoked, even charges of supporting terrorism against one of the group’s members. We should expect more of these as capitalism’s more illiberal phase takes shape.

We must also understand that at stake is a fundamental question about art in late capitalism. Who gets to make art? What kind of art do they get to make? What purpose will it serve? Will it ferment the human subject apart from the rule of capital? Or will it become a soundtrack to the subject’s confinement?

Where one stands on these questions will likely tell us where they stand on a host of other matters. Key among them: socialism or barbarism.

Header/background image is by Laura Oldfield Ford. All other images were used in presentation slideshow.