An observation: in today’s world, “pretentious” is normally code for “this is something I would rather not think about and therefore I am going to judge it harshly without considering it.”

During the 2016 American presidential election, a poll was conducted that jokingly included an option for a giant meteor. In other words, it was asked whether potential voters would rather a massive asteroid collide with the Earth than any available candidate become president of the United States.

The poll found that 13% of those surveyed preferred the meteor. Hillary Clinton received 39%. Donald Trump – the eventual victor, as if we need reminding – got 35%. The meteor got a higher percentage than any of the third party candidates who actually appeared on the ballot.

On the surface it’s comedic. In that bitter, sardonic kind of way. It naturally says something about the unpopularity of both Clinton and Trump and the intransigence of the American political system (now might be the right time to reiterate that had the Democratic establishment not been so characteristically terrified of the specter of socialism, Bernie would have indeed won). But in my estimation it says something even broader and more fundamental.

Apocalypse is no longer something in a far-off, speculative future. It is an undeniable part of the now. Beneath the insufferable shiny-happy insistence of advertising, “official” politics, and the fantasies of billionaire moguls, the notion of an unfolding/ongoing catastrophe is woven into just about every facet of culture and common logic. Attempts to cover it up just make it that much more unavoidable and dark.

Nowhere

In 1890, William Morris published what is arguably the first successful example of modern communist speculative fiction: News from Nowhere. As much propaganda as pulp literature, it was written as a direct response to Edward Bellamy’s technocratic socialist vision Looking Backward. In it Morris reimagined London through a radical lens that as free of pollution, poverty, and theft of time.

There is plenty in the book that we would find simply outdated, in particular its portrayal of women. But News from Nowhere was a sincere and creative attempt to pivot from the degradation of industrial capitalism. It was naturally imbued with the romantic Morris’ nostalgia for pre-capitalist pastoralism, but it also self-consciously avoids unproductive wistfulness that pines for turning back the clock. The radical’s view of history as an overlapping and cumulative process is what allows the book’s incorporation of sustainability and egalitarianism come alive. News from Nowhere personifies the Marxist’s ambivalence toward modernity: savvy to how its productive capacities made possible real equality and solidarity, horrified at how its hierarchies produced unprecedented degradation

The book’s very title was a nod to its first-glance infeasibility: “utopia” being translated literally, prior to Thomas More, as “nowhere.” As in “nowhere exists this type of world.” But Morris’ sly trick was to pull this out of the realm of absolute fantasy by adding a subtle “yet…”

There is, of course, an adjacent apparent impossibility to cobbling together a utopian vision with a dystopian reality; two conjunctures that cannot coincide. Indeed at first they seem diametrically opposed. But there was also a time not so long ago when the dystopian seemed equally far-fetched and far-flung as its mirror opposite.

Reality has intervened, and not for the better. Climate change has accelerated, making food scarcity, droughts and devastating floods a fact for huge swathes of the globe. We know that we have already crossed the point of no return for a warming planet. The degradation of soil, should it continue, will leave the planet with perhaps 60 full harvests.

Mass refugee crises, never-ending war and the shuttering of borders are casually woven into news coverage and polite conversation. The line between the unimaginable and reported reality disintegrates.

Insipid morning show hosts might try to soften the blow, telling the inspirational story of the exceptional suburban mom doing food drives for refugee kids, or move quickly from coverage of the UN’s latest predictions for climate catastrophe into that day’s guest celebrity chef. But cultural awareness never takes things at face value. Deep down, we know we’re fucked. Remember ten years ago when Children of Men seemed more an eerily prescient warning and not a portrayal of the world as it is? Fun times…

In other words, catastrophe is everywhere. Giant Meteor 2016 isn’t just an instance of dark comedy. It is, indirectly anyway, a reflection of the connection between persistent devastation and the persistence of a political and economic system whose pretense of a plentiful/prosperous future is on very shaky ground. It is a 21st century version of Amadeo Bordiga’s reminder that rich people also drowned with the Titanic. If we can’t stave off impending doom, at least we can take solace in the fact that mismanaged capitalism will eventually overtake those who have subjected us to the fallout of mismanagement.

Of course it’s never that simple. The rich passengers aboard the Titanic disproportionately were able to get to lifeboats, unlike the poor folks in steerage. Should the planet become uninhabitable, it’s entirely plausible that the ruling class will be able to construct their own Elysium. That’s precisely the motivation behind such projects as Eko Atlantic in Nigeria and others like it. More often than not they will find a way to shield their selves and their lifestyles from consequence. We, as always, get the wreckage.

The dystopian is already a reality. The impossible has once again proven possible. Any kind of useful realism must, therefore, take this dynamic into account, seeing the utopian not as a dream, but as a demand.

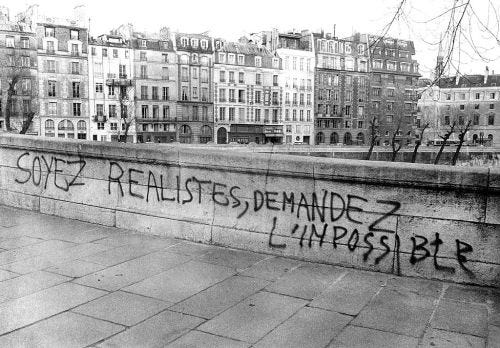

So did the writing on the walls remind us in Paris, 1968. This blog is an attempt to cobble together – sloppily, perhaps self-indulgently – one aspect of a dys/utopian praxis: the vivid radical imagination; one that isn’t so much an escape as it is an escape plan.

Devastation

What I am here calling “dys/utopian” is hardly groundbreaking. And I can’t take credit for it. There are other writers and publications on the contemporary Left who have been exploring this for at least a few years prior to my starting this blog. Evan Calder Williams’ Combined and Uneven Apocalypse comes to mind. So does much of the work of the recently and tragically departed Mark Fisher, whose notion of “the slow cancellation of the future” has been essential in forming the ideas here.

Enzo Traverso’s recent book Left Melancholia attempts to salvage the dreams of a fractured Left in the midst of capitalism’s perpetual false starts. And, as long as we’re using the term, I can’t pass up the chance to mention the always-indispensable journal Salvage.

All of the above are brilliant attempts to forge some kind of intellectual and material praxis for a Left that has had the reset button hit on it. It’s my hope to add to this in a constructive way.

The enumeration of the above atrocities has normally provoked a familiar refrain: “It doesn’t have to be this way.” True of course, but insufficient. Is another world possible? It is unquestionably necessary, but its feasibility is by no means a given. The planet has already passed several points of no return with climate change, which in turn brings each future turning point closer with increasing speed.

This quickly approaching mass historical moment is ironic considering the past few decades of capital’s trajectory. Ever since the collapse of “actually existing communism” we have been stuck in a kind of momentous feedback loop. Neoliberalism’s adaptability means that its undead husk can keep shuffling on indefinitely. As long as it does, its cultural logic – the declaration that the new can never really be new – drags along behind it. The pressure for us to be “flexible” with our time, to accommodate more of our lives to accumulation of profit, grows greater. Crises worsen, but they don’t stop happening. Disasters stop being benchmarks and start being daily occurrences folded into our routine.

Perhaps we should have seen it coming: the problem with “the end of history” was always that it wouldn’t be able to stop starting.

The question (a very open one in fact) is whether the Left, that contingent who historically have fought the hardest for things to not be this way, can manage to break out of the feedback loop. Whether it can get creative and do things differently. Whether it can gain the wherewithal to soberly assess the already-existing wreckage around it and figure out how to repurpose it, to become the coming catastrophe so that it is only society’s rulers caught up in it rather than ourselves. Either we continue to allow the monuments to be built on top of the rubble with us inside it, or we figure out how the build our own from the same refuse.

Revolution

Others have said that the Left’s present state is one of devastation. This is obviously fitting given the general state of things. Just as the working class has had its coherence and institutions robbed of it, so have Left and revolutionary organizations found themselves sidelined and treading water. For sure, there are green shoots of hope for those who wish to end this state of affairs: the election of Corbyn as head of the Labour Party in the UK, some victories for Leftist parties in Europe and elsewhere, the Sanders campaign in the US and the explosion in popularity for socialist ideas in its aftermath.

These are the most hopeful signs for radical renewal in decades. They are also not enough, and are emerging in the midst of odds that remain slim. Can socialism be won and built when half the planet is a sacrifice zone? We may have to address this question in real time, and we will not be able to do so by relying on the same answers we always have. A level of cultural sophistication and vision – the kind which has not been so much lacking as it has been forgotten in the midst of the great neoliberal shakeup – is urgently needed.

Now the inevitable question: will this be a project of doom and gloom? To a certain but ultimately limited degree it has to be. It is not, however, melancholic. I would rather characterize it as being grounded in the thought of Marxist writers and activists whose sensitivity to culture opened them up to a practical revolutionary pessimism: Antonio Gramsci, Walter Benjamin, Anatoly Lunacharsky, André Breton, José Carlos Mariátegui, Suzanne and Aimé Césaire, Pierre Naville, Raoul Vaneigem, Frantz Fanon, Michael Löwy.

All of these figures possessed zero faith in the possibility of capitalism to provide any salvation. All knew that the act of mourning, of recognizing just how much we have lost and just how bad it has gotten, was an unavoidable step in grasping radical social change.

All knew that reforms were only a delay of the inevitable. All saw revolution (to borrow from Benjamin) as the handbrake preventing history from careening off a cliff, partaking in revolutionary thought and action not because it filled them with optimism but because it was the only way path toward basic survival.

Finally, all saw in artistic expression the ability to psychologically straddle the gap between the real and the visionary. A widening of the field of imagination, revealing the machinations of capitalism as intrinsically corrupt but also for a more vivid notion of revolution.

Culture is an expression of the economic and political substructure of society, but this does not mean it is static. Its relationship is, in fact, quite far from the Manicheanism that has plagued Left frameworks on arts and culture for decades. Being able to put aside this wooden, almost caricatured method allows for the dynamic to be revealed. For the possibilities, however dim, to animate. For contradiction to cease being just something that merely exists and to become the key to rupture and liberation.

I would contend – and will do so repeatedly on this blog – that we are surrounded by contemporary cultural artifacts that reveal this multifaceted character: marked simultaneously the brutality of the past and present, and the fading prospects for a future worth living. Much like Morris’ time-traveler, our starting point must be now, but if we aren’t daring to rigorously think through the implications for a radical vision, then there isn’t any real reason to ponder in the first place.

Or, on the other hand, maybe it really is all just pretentious. But pretense is a right, not a privilege. And sometimes a giant meteor is just a giant meteor.