For most of November, I was on my honeymoon in Spain and Portugal. You would think that means I take a break from the obligations of writing and cultivating an audience, but no. I cannot, for whatever reason, tear myself away from this neurotic need for a forum. The upshot is you get to watch me attempt a travel journal as I journey from Porto down to Lisbon, into Spain by way of Seville, up the eastern coast, into Barcelona. Old buildings. Efficient trains. Conversations with total strangers. The first and second in the series can be read here and here. Also, if you haven’t subscribed or upgraded to a paid subscription, this is your cue.

X.

The story goes like this. She worked as a coat checker at a Lisbon restaurant. On the morning of April 25, 1974, she showed up for her shift, which was expected to be busy. It was the first anniversary of the restaurant’s opening, and the dining room was bedecked with red and white carnations. But when she arrived, she was sent home by her boss.

He had been listening to the radio, and word was spreading fast that something big was happening. The kind of event that would make doing business impossible. So he sent her home. On her way out, he shoved a bunch of the red carnations into her arms. He didn’t want them going to waste.

Walking back to her apartment, she saw what was happening. It was no longer just on the radio, but in the streets, flowing out of homes and businesses. A row of tanks and armored cars headed toward Largo do Carmo, where Marcelo Caetano, head of the far-right authoritarian Estado Novo regime, was holed up with loyal generals. This was the Armed Forces Movement (MFA), who had been planning a coup against the Estado Novo for more than two years.

Citizens poured out of their homes waving flags, cheering the MFA on as word spread that the government was about to fall. She cheered them on too. This was a hated, rickety regime. Literally rickety. Caetano’s predecessor, Antonio de Oliveira Salazar, the cold and venal man who had ushered in and overseen the Estado Novo for forty years, had been incapacitated when he sat on an unstable chair in 1968. The chair collapsed, and Salazar had a cerebral hemorrhage. He died in 1970.

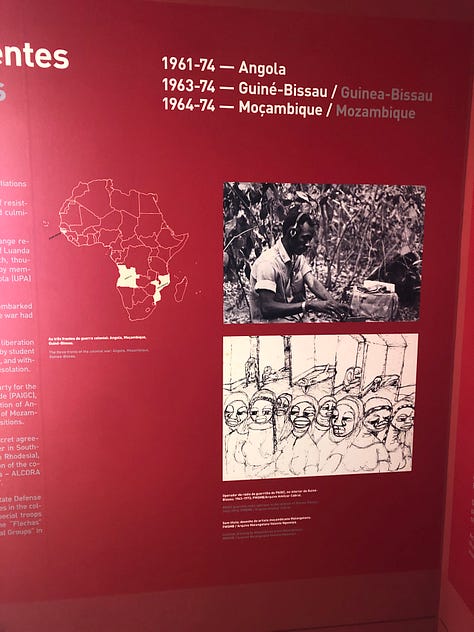

Caetano took over, but nothing in the Estado Novo stabilized. Portugal’s colonies on the African continent – Mozambique, Angola, Cape Verde – were in open armed rebellion against Portuguese rule. By some estimates, 40 percent of the country’s budget was being poured into suppressing these movements. Everyone, especially the poor, had known someone drafted and sent to shoot at other poor people. Likewise, everyone had known someone disappeared by the country’s hated secret police, the PIDE.

As the tanks and soldiers passed by, one of them asked her for a cigarette. She said she didn’t smoke, and gave him one of the red carnations instead. He chuckled and put the flower in the barrel of his rifle. Soon, other soldiers were approaching her, asking for their own carnation to carry with them on their way to topple a government. Hours later, Caetano and his generals had fled, and the military was in charge.

The democratic outpouring was massive, seeping into every facet of daily life. The next eighteen months would see thousands of mass strikes and demonstrations. Factories were occupied, rural farms taken over by employees. There were experiments in workers’ control and self-management, communist and socialist parties flourished. Laws established a thorough welfare state, guaranteeing healthcare as a right and nationalizing whole industries. It was a fulsome revolutionary process, radical and far-reaching.

It was only halted by a right-wing counter-coup in November of 1975, led by more conservative members of the MFA, known as the “Group of Nine.” Elections were held the following year. The Carnation Revolution, named for her flowers, came to be trapped in amber, mythologized into a more or less orderly transition to representative democracy, minus the insignificant flurries of chaos. A blueprint for the velvet revolutions that came fifteen years later.

Her name was Celeste Caeiro. She died on November 15th, the day after we arrived in Lisbon. Though she hadn’t been directly involved in the planning of April 25th, she had aided resistance to the regime. When she was a teenager, she discovered clandestine leftist meetings had been taking place at her uncle’s house, and joined in. She smuggled banned books into the country in packets of tobacco. On the day of her death, the Portuguese Communist Party – of which she was a member – released a tribute to “Comrade Celeste.”

Her children and grandchildren reported that she often felt overlooked for the role she played, though she was center-stage at some of the official 50th anniversary commemorations of the revolution this past April. Now 90 years old and wheelchair-bound, she was accompanied by her daughter and granddaughter. That same day, in the Assembly, deputy Rui Tavares of the left-wing LIVRE party suggested erecting a statue in Lisbon in Celeste’s honor.

XI.

Whenever I go to a new city, I read as much as I can of its literary legends. In Prague, I read loads of Kafka. He is everywhere in the city: plaques, sculptures, at least one museum. These feel like invitations to converse with the city’s layers of history.

For Lisbon, I went back and read Jose Saramago. He loved the city dearly, and lived there most of his life. In 1978, he published “The Chair” as part of his collection The Lives of Things. The story homes in on a specific mahogany chair that, through generations of woodlice, has become unstable. It tells the story of the chair’s slow decay until, one not so very special day, it is sat on by a certain dictator.

A sick but happy accident of history? Or did the chair know something? Perhaps it conspired with the bugs that were slowly chewing its wood to pulp? Either way, the clear takeaway is that a human being can only stay in place for so long.

Saramago’s stories are filled with these kinds of moments, and characters prone to them. People touched by the absurdities and happenstance of history who either decide to use it to their advantage or are completely inundated by them.

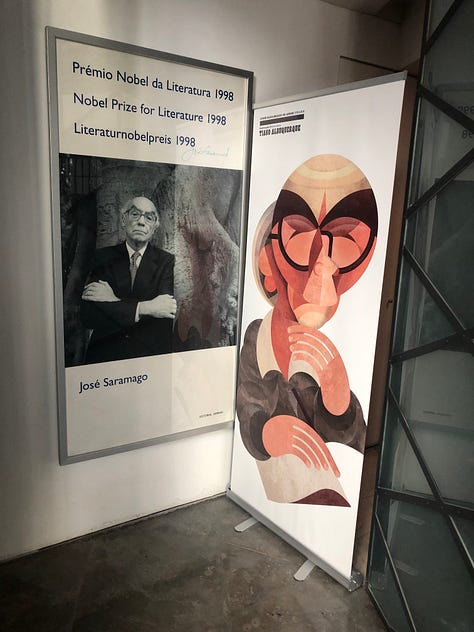

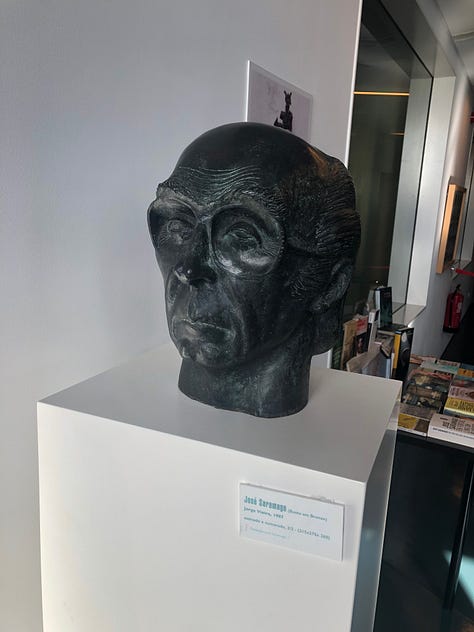

There are no statues of Saramago in Lisbon’s public squares. It might be just as well; Lisbon is already full of statues. Still, save for the small, unassuming tree where some of his ashes are scattered, Saramago doesn’t show up much in the city’s public life. This man, for whom memory was something sacred, is relatively tucked away. The one notable exception is the Jose Saramago Foundation, just across the square from his ashes, housed in Casa dos Bicos in the Alfama neighborhood. Constructed in the 16th century and rehabbed in the 20th, its thick glass floors gaze down into the ruins of an ancient Roman fish processing site, thought to be the first place that garum was made in Portugal.

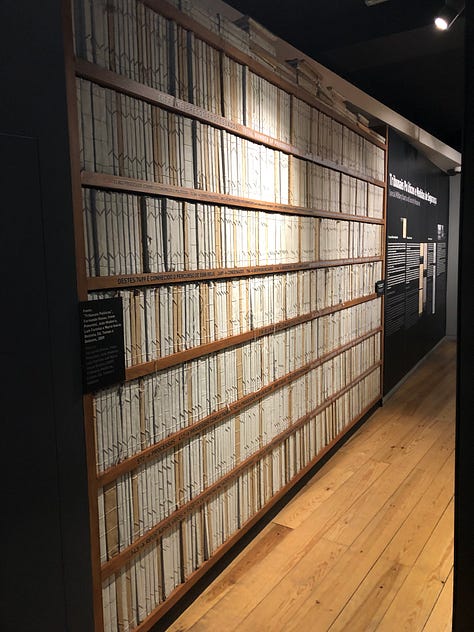

The Saramago Foundation occupies the upper floors of Casa dos Bicos. It houses a permanent exhibition on his life and work, featuring, among other things, walls covered in different editions of his books, in countless languages. It is remarkable to think that Saramago, who in 1998 won a Nobel Prize for Literature, only published one novel before his fifties. Prior to the Carnation Revolution, he had worked primarily as a journalist and newspaper editor.

A year after the fall of the Estado Novo, amid the ongoing revolutionary process, Saramago was promoted to assistant director at Diário de Notícias, one of Portugal’s oldest and most respected newspapers. Saramago guided Diário in a strong pro-communist direction, though this line was halted after the right-wing counter-coup of November 1975. Saramago was sacked. He returned to writing novels, and in 1988, his Baltasar and Blimunda made him an internationally recognized author. Four years later, Portuguese Prime Minister Aníbal António Cavaco Silva had Saramago’s The Gospel According to Jesus Christ removed from consideration for the Aristeion Prize, arguing it offended Catholic sensibilities. Saramago moved to Spain in protest, and stayed there until his death.

Saramago’s face and name may not be scattered around Lisbon, but Fernando Pessoa’s is. I’ve never read a word of Pessoa. I know he was a massive influence on Saramago, along with most other Portuguese writers from the mid 20th century on. The titular character in Saramago’s The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis is named for one of the many pseudonyms Pessoa used.

After a few days in Lisbon, Mrs. Daydream and I figured it was time for us to familiarize ourselves with Pessoa’s work, and to see if there were any other Lisbonian poets or novelists who merited our attention. We went to Livraria Bertrand, which markets itself as the world’s oldest bookstore. That title is held only by the flagship location, though. We went to one of its chain locations near our hotel.

There, we met Ines and Camila, two young Bertrand employees eager to talk literature and politics with us. They recounted the huge celebrations and festivities held in April on the 50th anniversary of the MFA’s coup. They went on for days — parties in the streets.

Prior to this, I had been struck by the lack of interest in discussing the Carnation Revolution. Yes, posters and artworks celebrating the 50th anniversary were everywhere, but nobody seemed interested in talking about it. Not that it’s the responsibility of a city to rehearse its history for tourists. I’m not sure what I had expected. Nonetheless, it made me wonder if the event had been so quickly sanitized of meaning and relevance, another day off work (if you’re lucky enough) without much in the way of substance. Like the Fourth of July back in the States.

It was Ines that informed us of Celeste Caeiro’s death earlier that day. She also spoke about how expensive Lisbon had become for its residents. We mentioned Donald Trump’s reelection and the high cost of living in the US had prompted many of the country’s older, more comfortable and more liberal residents to consider living abroad. Portugal had become an attractive option. It’s cheap and has a high standard of living.

While it might be cheap by American standards, the influx of well-off ex-pats had driven up the cost of rents across Portugal, particularly in Lisbon. Wages, meanwhile, had stagnated. For most Portuguese, living standards have been essentially frozen since the debt crises of the late aughts and early 2010s.

Ines was quick to say that she thought everyone who wanted to live in Lisbon should be able to, but allowing landlords to take advantage of the fact was making life impossible for residents, including people who had lived there their whole lives. I was struck by how open and frank she was. During our conversation, I kept looking over my shoulder to ensure her supervisor wasn’t skulking around.

XII.

Americans with an interest in the lusophone world love to talk about saudade. Part of it is that we love words that don’t have a direct translation into English. Makes it feel exotic and mysterious. It’s more than a bit infantilizing too, which no traveling American is really able to avoid. Nor will we be able to until our own empire has been thoroughly cowed.

There’s a further reason Americans love the idea of saudade. The word is roughly defined as a feeling of incompleteness, a longing for something or someone that is absent. Naturally it’s a mood colored by nostalgia and melancholia. It naturally provokes some obnoxious reactions. This dipshit is complaining about how sad everyone seems to be in Portugal, bemoaning the fact that there’s even a music genre (fado) dedicated to themes of loss and longing. One wonders if he has ever lost or longed for anything or if, like most dipshits, is either too privileged or stupid to know the feeling.

For the most part though, the reaction of Americans is one of romanticization. And why not? The idea of absence as an ontological state is a very familiar one by now. It is also a handy aid in subjugation, a way of naturalizing the voice in your head that says you’ll never have this. It’s a perfect state of mind for the post-neoliberal subject. Nostalgic, resigned to deprivation, vulnerable to bouts of anxiety and manic accumulation where, try as we might, we only end up enriching someone else. The frustration turns to melancholy. Rinse and repeat.

Except that this doesn’t actually capture the full implications of saudade. It doesn’t capture the frame of mind of people like Ines, or Saramago, or Celeste Caeiro. The tourist-friendly version of the term is solipsistic. This may be unavoidable; saudade is, after all, derived from the Latin word for isolation. But this understanding effectively erases the context necessary for these feelings. To feel incomplete, one must have at least a vague understanding that they can be made complete.

In this respect, saudade is defined as much by what is absent as it is by the feeling of absence itself. A feeling brought on when events decide to reach down and touch you with their cruel denial. And so you wait, longingly, hopefully, for the next time they touch you, when you might have a chance to regain what you lost.

XII.

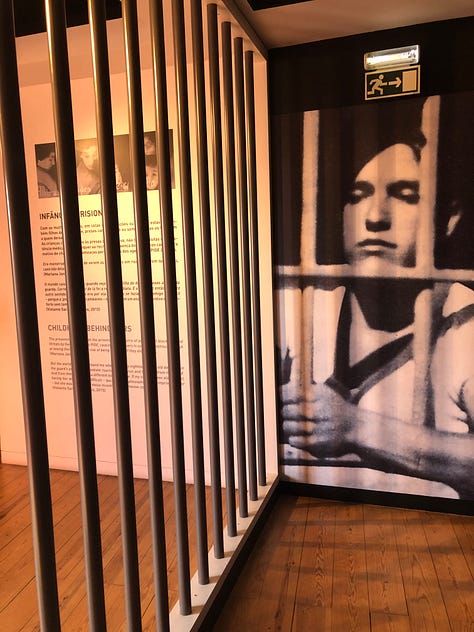

The Aljube Museum of Resistance and Freedom – or, in Portuguese, Museu do Aljube Resistência e Liberdade – is housed in what used to be a prison. Dating from the Moorish era, its name is derived from the Arabic al jubb, roughly translating to “dungeon.” Up until the 1500s, it was an ecclesiastical prison, where the Catholic Church would lock up misbehaving monks and priests. In the 1800s, it became a women’s prison. After the Estado Novo came to power, it was where political prisoners were incarcerated.

A relatively small building, its permanent exhibits are extremely well-curated and relatively claustrophobic. This is apt. Its first floor features recreations of the tiny cells prisoners occupied. When walking into the exhibit, a harsh alarm bell sounds. Testimonials from former inmates play on monitors. The effects of their trauma are evident. Recounting their stories, it is all too easy to see their eyes glaze over in bewilderment and awe that time had selected them to endure such madness and cruelty.

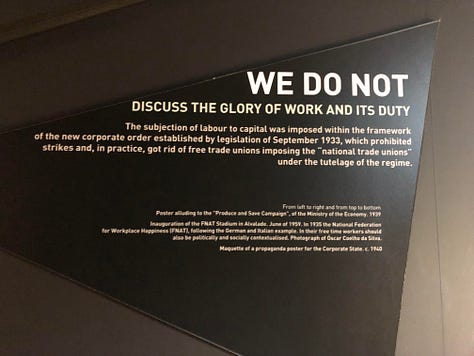

Another floor chronicles the rise and rule of the Estado Novo. The bullet points of Salazar’s 1936 “great certainties” speech are displayed. They paint a bleak picture of the kind of repression and censorship, the kind of cultural forgetting, that his regime enforced in public life. “We do not discuss God and his virtue.” “We do not discuss the homeland and its history.” “We do not discuss authority and its prestige.” “We do not discuss the family and its morality.” “We do not discuss the glory of work and its duty.”

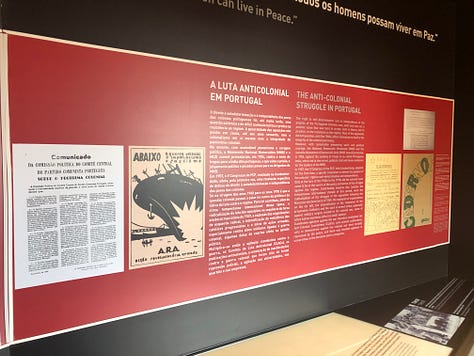

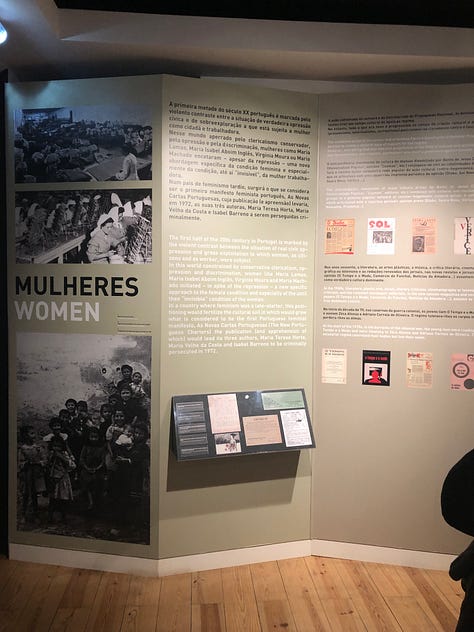

Further rooms and corridors are dedicated to the persecution faced by trade unionists, women, intellectuals, and artists. Several rooms specifically chronicle the torture methods used by the regime against dissidents. A long hallway features walls of logs and files emulating those kept by the PIDE. By some accounts, the secret police had as many on its payroll as the East German Stasi did. An entire floor profiles the Estado Novo’s severe repression and exploitation of Portugal’s colonies abroad.

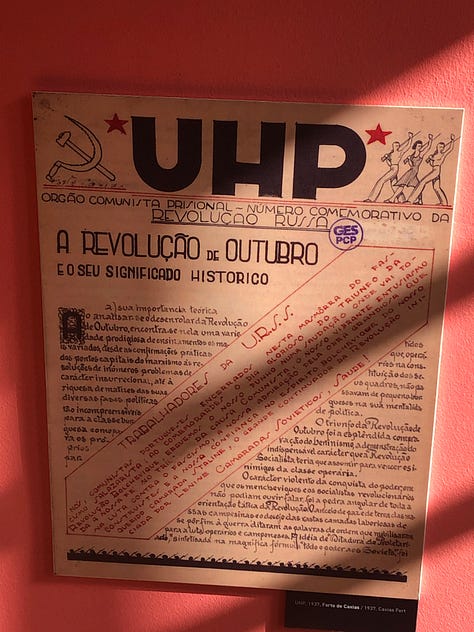

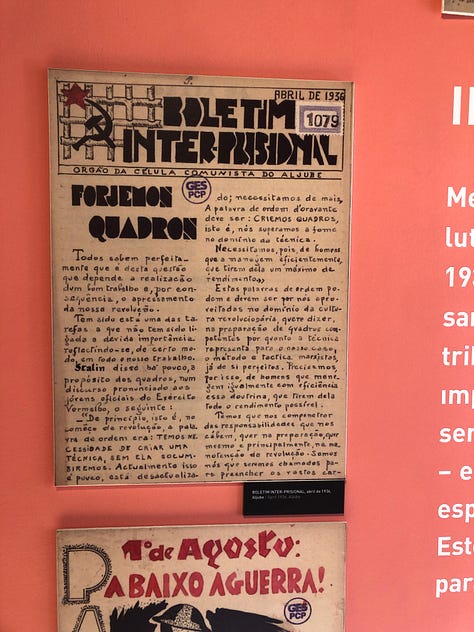

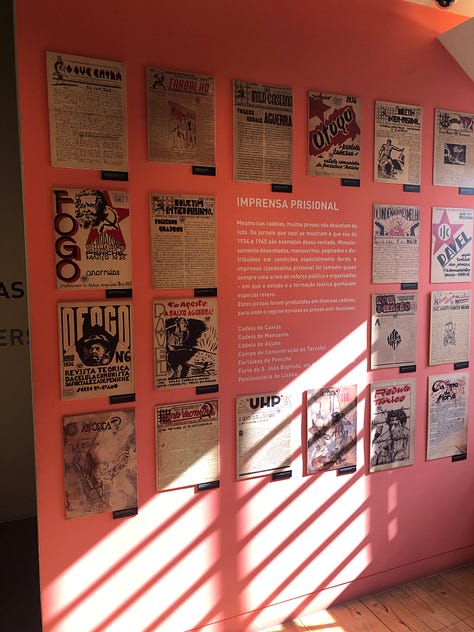

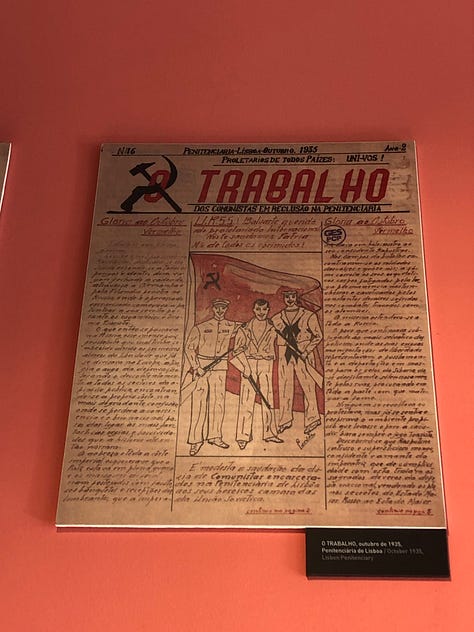

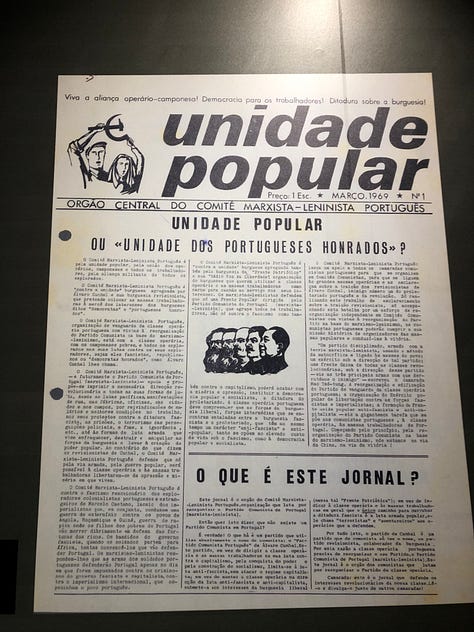

However, this is a museum dedicated to resistance. Rebellions among sailors, peasants, industrial workers, women, and students are recounted. Anticolonial organizations like Angola’s MPLA, FRELIMO in Mozambique, and Cape Verde’s PAIGC play a large role in the floor dedicated to the colonies. Walls are filled with copies of underground newspapers opposing the Estado Novo.

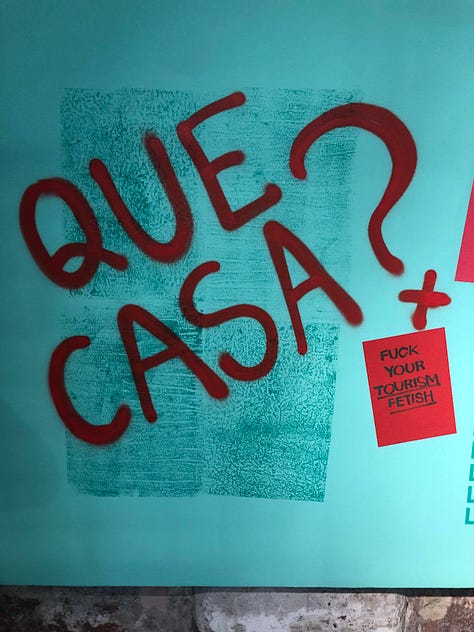

Then there is the special exhibit on April 25, less a recollection than a celebration. The room is painted a bright turquoise. Some banners and placards are suspended from the ceiling. Others are painted on the wall. Some read “25 de Abril Sempre! Fascismo nunca mais!” “Unidos contra o fascismo,” “Liberdade!” Slogans directly related to the overthrow of the Estado Novo, though some, pointedly, could just as easily show up today. Others are more directly related to the activism of the 21st century: “Capitalismo nao e verde,” “Girls just want to have fundamental rights.” There’s one that reads, pointedly in English, “Fuck your tourism fetish.”

In one corner, there is a steel frame with large canvas flaps that can be flipped through, recounting the events around and relevant to April 25. This includes many of the strikes and demonstrations, and a few of the factory occupations. It also includes the defeat of the revolutionary process on November 25, 1975. In another corner, the more interactive part of the exhibit: a metal grille with pieces of paper bearing slogans and drawings made by visitors. Nearby is a table with paper and markers. Some of the papers are of red carnations and mention April 25 specifically. Others are relevant to housing rights. Several mention a free Palestine.

It’s all very nifty. If nothing else, the vibrant colors manage to contrast with the dark blacks, browns, and grays that seem to predominate in the rest of the museum. The switch from bleak and repressive to free and colorful is no doubt intentional. Likewise, the curators clearly aim for attendees to draw parallels between yesterday and today. It is quite explicit that they believe that contemporary struggles around climate change, housing, and economic justice are a kind of continuation of the overthrow of the dictatorship 50 years ago.

The deliberate inclusion of the events after April 25, the protests and fights around exactly what future lay ahead for Portugal now that it had been opened up, is in this regard crucial. In general, the Aljube goes to great pains to emphasize that the people of Portugal and its colonies weren’t passive victims. They resisted. They fought. They did their best to live with dignity, and when the regime denied them that dignity, they sought ways around or through.

Better than a statue. Still, exiting through the gift shop (I bought a poster and a keychain) and into the Atlantic sunlight, being immediately confronted with ugly billboards prying cash from our hands, lines of tourists braying for a taxi, you are reminded how insufficient it all is. Maybe that’s on purpose, but it’s certainly unavoidable.

XIV.

In the conclusion of her book A People’s History of the Portuguese Revolution, Raquel Varela asks why it is that Chile weighs more heavily in the left’s imagination than Portugal. The coup and massacres that toppled Salvador Allende’s democratic socialist government had taken place just six months prior to April 25. Satisfied as Kissinger and others in the American and Western European political establishment were with the results, they looked to Portugal with massive anxiety. Writes Varela,

The Portuguese Revolution was a social explosion that US president Gerald Ford considered capable of transforming the entire Mediterranean into a ‘red sea’ and causing the downfall of all of the regimes of southern Europe like dominos. We can argue today that it began a wave of resistance in southern Europe that delayed the implementation of neoliberal plans attempted from 1973-1975 until the crisis period of 1981-1984.

This may help explain the prevalence of Chile over Portugal in the conventional imagination. Chile needs to be remembered as not just a failure but a bloody massacre, a cautionary tale of what happens when you reach for something better. Yes, the US eagerly backed the Group of Nine in Portugal and their designs for November 25, but they did so knowing that the Group would not be able to pull off the same bloodbath as had been seen in Chile (nor did they particularly want to).

On the other hand, even in its defeat, the Portuguese revolutionary experience had been more successful. Not only was there an aversion among the Group of Nine against repeating what Pinochet had done, there was also the distinct fear of backlash. The committees of workers and soldiers were simply too strong, the possibility of an open rebellion, possibly even a civil war, too great. The process of winding down radical workers' organizations had to be done carefully, and elections of some sort couldn’t be far behind the coup itself. Even so, the massive gains of the revolutionary months – universal health care, housing as a right, a certain amount of deference to unions – were considered untouchable by policymakers of all stripes. Some The economic crises of the 1980s started to change that, but only in a limited capacity.

The crisis following the 2008 economic collapse provided far more room to attack this robust welfare state. Hence the skyrocketing rents, the deteriorating hospitals, the same anxieties and malaises we hear from all over Europe and the world right now. Every single thing having to do with this city reified, turned into its most sellable self. Buildings and objects moving in place of people.

Hence the worrisome, almost amnesiac backsliding. All over Portugal you can see this man’s stupid mug:

That’s André Ventura, a far-right politician with kind things to say about the Estado Novo. His Chega party, promoting itself as the party of “God, fatherland, and family,” achieved a stunning breakthrough in the most recent elections, gaining 50 seats in the national Assembly. The parties of the left – LIVRE, the Communist Party, and Bloco de Esquerda – hold a combined 13. There is a palpable nostalgia for Salazarismo. Perhaps it was always there. Most statues of the man have been brought down, but that doesn’t seem to matter right now.

XV.

The past weighs like a nightmare on the present, but the opposite is also true. A broad survey of the world now seems to reveal nothing but foreclosures on the possibility of revolution. The rise of Chega in Portugal happens in context. Meloni in Italy. Milei in Argentina. Modi in India. Orban in Hungary. Trump. In both France and Germany, the far-right waits in the wings while the liberal establishment totters. The list goes on. It would appear that the side of reaction and counterrevolution has a decisive upper hand right now.

Richard Seymour, in his new book Disaster Nationalism, argues that the far-right, in its current phase, has figured out better than any other political current at this moment how to mobilize people’s minds: their emotions, their passions, their fears, their deepest psychological compulsions. Whatever you call it, the apocalyptic revenge fantasies of this not-quite-fascism are able to speak to it.

In the face of this, mere bread and butter fall short. The left, such as it is, doesn’t just need to offer more. It needs to offer something paradigmatically different: a life beyond isolation and domination by things. That is, something utopian. At least that is what the left has had to offer at its most successful, and it can happen quite organically.

“I think there is a legitimate, innate striving toward transcendence that is immanent to life as such,” Seymour tells Jacobin. “In other words, to be alive is to be striving toward ever another situation.” Later, he continues:

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels talked about this dialectic where you join a union initially for something like higher wages, a shorter working day, things that you basically need, but then you develop other, richer needs. Quite often workers will go on strike to defend their union even if they’ll lose wages and their objective material conditions will get a bit worse. They need one another, they need their union. It can go further; it can be politicized in a much deeper way. The most radical need is the need for universality, in a Marxist sense.

That vision, practical and unsentimental, can also be utterly awe-inspiring, a glimpse at levels of fulfillment currently foreign to us. Without it, there is no worthwhile strategy for a future. The crashes of history create desires that can either be diverted or redeemed through experiences of concrete solidarity, of which these bonds and connections are the atomic unit.

This is not for a moment to suggest we do not need history – histories from below, people’s histories or histories of struggle. But envisioning forward and learning to see history clearly are inextricable. It’s through them that the unmovable objects of our lives, the impenetrable walls of our surroundings, become movable.

The signal for the beginning of the MFA’s coup against Caetano, the alarm bell that initiated the whole process, was a song. The officers had recruited a late-night radio host to their cause. At midnight on April 25, he played "Grândola, Vila Morena." It was the signal for the tanks to roll.

This is not an outwardly “political” song, though Zeca was a musician of the left. The officers of the MFA opted against playing one of his more strident songs because they thought that would arouse suspicion. In any event, most of those songs had been banned. Why this specific song was chosen is a matter of debate, but it is a very simple one, with a straightforward narrative.

It is sung a capella, in the style of Cante Alentejano. Other than Afonso’s voice and the backing vocals, the only sound is boots walking on gravel in a steady rhythm. Afonso was moved to write the song after performing in Grândola in 1964. The town had a reputation for protest against the Salazar regime, and a certain resilience among its residents in supporting each other. That is what Zeca wrote about. There are no slogans in this song, no grand political pronouncements, calls to arms, stories of strikes or protests. Just a simple melody telling a simple ode to a place where there is “On each corner, a friend. In each face, equality.”

Walking around Lisbon makes for an uncanny experience with all of this mind. It isn’t easy to look at the Avenida de Liberdade, the grand boulevard of Lisbon, without picturing tens of thousands of soldiers and civilians marching on it, banners unfurling across the wide streets. Now, the street is populated by some of the most decadent names in luxury goods. Givenchy, Yves Sain Laurent, Dolce & Gabbana, Armani. The Lisbon headquarters of the Portuguese Communist Party is here. It’s next to a Gucci store.

XVI.

At the top of the Avenida is Eduardo VII Park, an ample, sprawling green space of more than 60 acres. Named for the British King during his 1903 visit, it is imposingly formal. People walk their dogs and play with their children on the manicured lawns and stately terraces, but it feels like we are here at someone else’s leisure.

Until we get to the top of the park. Here is the Monumento de Evocação ao 25 de Abril, a large, mostly abstract sculptural monument to April 25, constructed by the artist João Cutileiro. Large slabs of roughly cut marble jut from the ground. Two small pillars stand on either side, as if something else had just been there. In between, a large carnation carved from red Negrais and green Viana marbles. Normally, it operates as a fountain. When Mrs. Daydream and I arrive, it is surrounded by a chain link fence, the water turned off, awaiting proposed structural renovations.

This only adds to the feeling that something is unfinished here. We have to acknowledge it. We may well have had to even if the monument weren’t cordoned off. The sculpture has long been controversial. No doubt some in the city would prefer something less interpretive, more conventional, a direct representation rather than a symbol.

It’s not just that it feels incomplete, it’s that it invites you to impose yourself upon it, playfully opening the door for you to walk through. Here, at what feels like the top of Lisbon, you are compelled by what is essentially a scatter of oddly arranged rocks. If you didn’t know better, you would almost say that it’s asking you a question. Does this stone pile know something? Or is it simply waiting for the rest of us to understand? If only there were some exotic word for the feeling these kinds of thoughts provoke…

There is a quote from Saramago’s short story “Raised From the Ground” at the Aljube Museum. It is featured in the section of the museum examining the regime’s torture and interrogation methods. It reads thus:

Joao Mau-Tempo will stand still like a statue for seventy-two hours. His legs will swell up, he will become dizzy, he will be beaten with a ruler and with a baton, not that hard, but enough to hurt him, every time his legs gave way. He did not cry, but there were tears in his eyes, his eyes swam with tears, until even a stone would have taken pity on him. After some hours the swelling went down, but under the skin his veins stood out, almost as thick as fingers. His heart moved, turning into a thudding, deafening hammer, echoing inside his head, and then, finally, his strength totally abandoned him, he could no longer remain on his feet, his body bending over without him even realising it, and now he is crouching, he is a poor farm labourer from the estates, squeezing out one last feeble turd, Get up, you swine, but Joao Mau-Tempo could not get up, he was not pretending, this was another of his truths.

It is a harrowing passage. But note the way the narration switches, almost imperceptibly, between future, past, and present tenses. That’s not bad translation into English. Saramago’s stories frequently move like this. To him, temporality is pliable, at once immanent and grand historic.

Move time and you can easily move space. Like most imperial capitals, Lisbon’s rulers fancied the city the most important on earth, the hub around which the rest of the globe turned. Given its place on the westernmost tip of Europe, gazing out over the Atlantic, this was an easy belief to have. Riches literally floated their way into the city. To those on the African continent or Southeast Asia whose lives were torn apart in order to get those riches, this faraway Lisbon must have seemed a vortex, a gaping maw that devoured people’s lives. The end of all things. But no matter. The kings and dukes and burghers of the Age of Discovery built up their city with an eye to eternity.

Never mind that the city had been Moorish and Muslim just a few hundred years before. Never mind that a couple hundred years later, Lisbon would be almost completely leveled by a massive earthquake. The city would need to be entirely rebuilt. It was never the quintessential global city under capitalism the way it was during the mercantile age. It didn’t stop Lisbon’s architects from insisting upon it. Hence the statues.

There are, naturally for this year, red carnations everywhere, on walls and lapels and streets. Many of them will likely vanish in the next several months. But the winding roads and telephone poles and ancient churches and graffiti’d walls make clear the ability and necessity for things to change and reinvent in this city.

Time doesn’t stand still. Neither should any human being. Some part of us bristles at being turned from a being into a thing. We long to move. It’s the only way to be made whole, to be redeemed. Not in any mystical, spiritual sense. Not handed down by any sort of ineffable force, but discovered when we realize the motions of history can belong to us. Fifty years ago, this was a city where that happened, on a tremendous scale. Maybe it can happen again. Maybe not. It was. It is. But it never simply is because it was.

All photos by Kelsey Goldberg and the author.