Welcome to the second edition of “Worms of the Senses,” a (sort of) monthly feature where I reflect on the most notable things I’ve seen, heard, read, and thought in the past month. Last month’s “Worms” was for paid subscribers only. Maybe it’s the holiday spirit grasping my shriveled heart, but I’ve decided this should be a free feature. Also, if you haven’t yet signed up for a paid sub, now’s your cue.

Seeing…

Stalker, directed by Andrei Tarkovsky, screenplay by Boris and Arkady Strugatsky (1979). In retrospect, it’s rather surprising it took me this long to watch Stalker. Not only is it universally acclaimed as one of the greatest science fiction films ever, made by one of the undisputed masters of Soviet cinema, but Roadside Picnic (on which it is based) has had a fairly significant impact on my own writing.

Better late than never. Yes, Stalker is a masterpiece of modern sci-fi cinema. It belongs up there with A Clockwork Orange, Metropolis, Blade Runner, the first two Terminator films. There has already been so much written and said about it. How its story and tone seemed to predict the Chernobyl disaster. How effectively human ontology is rendered as something that can be estranged in odd, eldritch ways. I won’t rehash it here.

I will however say that making a three-hour film about our constant cosmic frustration with our human limitations should be easy. Not hard. Easy. Particularly when you embrace the slow pace of this melancholia. Yes, I know what I’ve written, and I stand by it. There is nothing more human than frustration with being human. It sounds trite for a reason.

But because most of us barely admit these thoughts to ourselves, effectively collectivizing them is a clumsy affair. It requires three hours of film. It requires sparse dialogue. It requires long and pensive shots. And through all of it, you need to be entertained, enthralled, mesmerized by your own boredom. What should be easy becomes near impossible. Tarkovsky pulled it off probably better than anyone else could have.

Say Nothing, created by Joshua Zetumer, airing on Hulu (2024). Even at the center of controversy, this series ran the risk of being utterly unremarkable, another transformation of history into moralistic finger-wagging about “the futility of violence.” Thank fuck it wasn’t. There is a real sensitivity and complexity brought to the (real) characters and to the (very real) terrorism they carried out as part of the IRA in the 1970s.

Calling it terrorism seems apt here, but only in its most descriptive, diagnostic sense. The starting point is that Northern Ireland was occupied, its Catholic citizenry discriminated against, and their right to resist it isn’t called into question. The efficacy of the means used to do so are a constant point of contention, but it never devolves into trite, boring “a plague on both their houses” territory.

Speaking with friends, I’ve compared it with The Battle of Algiers. Not in terms of the level of brilliance, but in terms of its willingness to portray brutal realities of resistance in a manner that neither romanticizes nor villainizes nor questions on which side you the viewer should ultimately fall. Given Gaza, given the controversial fanfare that continues to swirl around Luigi Mangione (more on that below), it is worth watching. I’ll also recommend this interview with showrunner Joshua Zetumer that appeared in Jacobin to further dig into it.

Wicked, directed by John M. Chu, screenplay by Winnie Holzman and Dana Fox, music by Stephen Schwartz (2024). I mostly despise musical theatre. Not because of what it intrinsically is but because of the role it’s come to play in our culture: a whole lot of singing and dancing designed for synthetic joy rather than the deep probing of human existence. The heightened psychological state of “I can only express this through song” makes for great opportunities, but most composers and writers fail to take advantage of them. They should be looking to work in the oeuvre of Threepenny Opera or Assassins. Instead they just want to emulate Andrew Lloyd Webber. Or at least that’s what Broadway producers choose to fund. Another reason Broadway is dying. Particularly now that Hollywood has rediscovered the musical format.

I assumed my experience of Wicked would mostly confirm this. Something about the amount of time during theatre school spent forced to listen to “Defying Gravity,” usually in that cloying, insipid, “please admire me” tone really soured me to it. Tragic. Mostly because it biased me against what is ultimately a very sharp and intelligent piece of theatre. In terms of the film, it's executed very well. The acting and singing are strong – including Ariana Grande but especially Cynthia Erivo. The art direction, costuming. and scene design are close to perfect, despite some unnecessary use of CGI. There are further, somewhat tangential thoughts on it in the “Thinking” category below.

Hearing…

Music for Psychiatric Wards and Fluid Structures by ADRA (2024). When we talk about how music changes space in a literal sense, this is a pretty good example. Andy Abbott made these compositions playing once a week in psych wards across Yorkshire over the course of 2023. He would walk in with an instrument or two, and, taking a cue from the mood, improvise. It’s eclectic, frequently relaxing, but also spiky and playful.

If we are used to thinking of ambient music as primarily electronic, this album challenges this notion. Some tracks, such as the one featuring the ambient music board (which, from what I can tell, is something Abbott built on his own), fall squarely in that colloquial definition. Others are more “organic,” using little more than a slide guitar.

Think back to Satie’s musique d’ameublement experiments, often viewed as the beginnings of what we now call “ambient.” No less a figure than Brian Eno sees the genre as continuing what Satie started. His intent was to spur different impulses in the listener, how they interacted with the room. Of course there were no synthesizers or effects because they didn’t exist in Satie’s day, but there is essentially no difference in aim. If Abbott walked into the ward and saw things too morose, he would improvise something more upbeat. If the energy was more chaotic or frenzied, he would play something to calm things down. Change the mood of the people occupying a space, change the space. Simple.

Mondo Decay by Nun Gun (2021). Nun Gun is a side-project of Ryan Mahan and Lee Tesche from the band Algiers and visual artist Brad Feuerhelm. It also invited guest collaborations from Adrian Sherwood, Mark Stewart (RIP), as well as a variety of other illustrators and artists. As you expected, it is one of those projects that really requires the full visual and audio to actually experience; Feuerhelm’s full 144-page photo book and the video for “Stealth Empire” are absolutely worth getting immersed in. Even without those, you’re still left with a strong example of harsh, dissonant/dissident industrial dub. Sherwood’s presence on the remixes of “Stealth Empire” is prescient in this regard; fans of his Dub Syndicate and Tackhead will probably dig this.

Nothing Can Stop Us by Robert Wyatt (1982). Is this Wyatt’s least cohesive album? Probably. But there’s a certain infectious charm to listening to him reinterpret some of the classics: “Strange Fruit,” “The Red Flag,” “Caimanera,” Elvis Costello’s “Shipbuilding,” Violetta Parra’s “Arauco.” Just about the only really unlistenable track is “Stalin Wasn’t Stallin’,” and not just for political reasons. That said, ending the album with Peter Blackman reading his poem “Stalingrad” is a quietly brilliant move.

Reading…

“The Tale of the Unknown Island” by Jose Saramago (1997). An impulse buy while at the Saramago Foundation in Lisbon last month. A puckish satire about rulers and dreamers masquerading as a lovely, whimsically mischievous fairy tale. Saramago is deft at the more surreal iterations of satire, reflected in his short-story collection The Lives of Things. “Unknown Island” is a bit more subdued at first than those works, but the story’s bite – a plain suggestion that kings and their courts are puzzled by nothing so much as their own self-knowledge – steadily comes into focus. This edition also has some lovely illustrations by Peter Sís.

Left-Wing Melancholia by Enzo Traverso (2017). This book has had more impact on me than probably 95% of the books I’ve read over the past decade. Adam Turl and I wrote a long essay that reviews and pivots from its arguments back in 2018. Most of those arguments, and those of the essay, are even more relevant now. Its core assertion, that the collapse of “really existing socialism” essentially broke the utopian dialectic of the 20th century, has only become more prescient in the years since its publication. Traverso never gives up on the communist ideal, or suggests that we should. But with no idea of a better world held out for us, the aims and strategies of the left have been unmoored. We have no choice but to try to cobble it together out of the wreckage.

It’s not altogether unlike the observations of Mark Fisher in Capitalist Realism: the elimination of an alternative from our sense of possibility, turning Thatcher’s adage into a self-fulfilling prophecy. It’s also an argument that holds a lot in common with the editorial outlook of Salvage (in fact, if I’m remembering correctly, Salvage ran an excerpt from the book not long after its debut).

The difference between when the book was published and now is obvious. It’s one of the reasons I thought now was the right time for a reread. There is, in a way, a viable competitor to the dead ends of neoliberalism. It will inevitably reveal itself as a mirage, though there’s no guarantee it will do so before it’s too late. But there’s no denying that Trump, whose reelection is indicative of the far-right’s undeniable and ongoing ascendance, has seized the imagination of a sizable portion of the world’s population. Its utopia is a sick one, depraved even, but it is creating its own dialectical pull against the deadening drone of late-late capitalism.

This isn’t to say it’s impossible for a renewed socialist vision to enter into this landscape. It will, however, be facing a more venal and unhinged version of capitalism than has possibly ever existed. In this regard, it is worth considering the melancholy of not just the subject matter, but its author. Traverso spends much of the book exploring how much of the socialist vision of the future pivots from the memory of defeats. Given the viciousness of the capitalism we’re about to face, it’s likely we’ll have no shortage of defeats to nurse. Whether we are able to cultivate an actual vision from them is an open question.

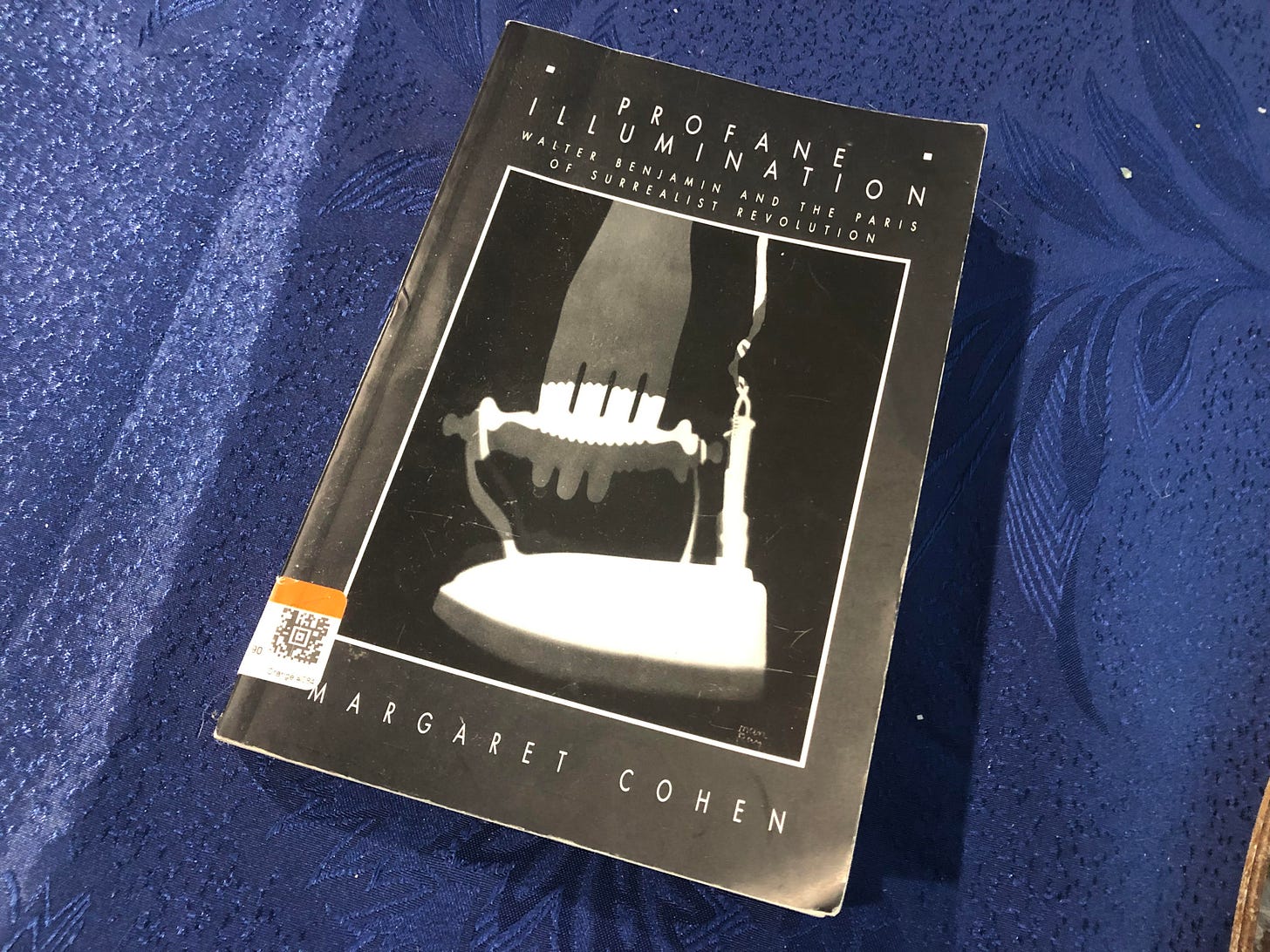

Profane Illumination by Margaret Cohen (1993). Rather a surprise it took me this long to read this book, but after being asked to write the piece on surrealism at 100 for Against the Current, I realized there was no further waiting. It is, bluntly, the best book written on the theoretical base of early surrealism.

Despite the subtitle, large parts of Profane Illumination are more preoccupied with the thought of Andre Breton than they are with that of Walter Benjamin. Breton is universally recognized as the primary early surrealist thinker, but short shrift is normally given to the actual substance of his thoughts. His Marxism held much in common with that Benjamin’s: bristling at the hidebound, paint-by-numbers thought of the official communist movement, less concerned with the realities of labor than by the various psychological repressions that would be eased by the end of work, entranced by the histories hidden in the geography of the modern city.

Cohen examines all of this, aiming to shed light on the meaning of gothic Marxism and the adjacent surrealist concept of “modern materialism.” Many of the conceptual spaces she opens up along the way probably merit their own book. There’s a chapter that relates the interaction between conscious and subconscious to the framework of base and superstructure. Other sections use Breton’s own books – Nadja, Communicating Vessels, Mad Love – to better illustrate place, person, and the strange psychological phenomena that emerge from their chance encounters. She also draws lines between these and thinkers who have rarely been considered in the same breath as surrealism or Walter Benjamin, in particular Louis Althusser.

Reading Profane Illumination in tandem with Left-Wing Melancholia also produces some interesting affinities. If we are, as I mentioned above, going to cobble together a viable socialist utopian vision that can vie for influence with capitalism at its most unconscionable, then we are going to have to grasp the histories of defeats, their lessons, and their redemption far more concretely. This, in turn, means walking down a city street and seeing the battles that took place there, even the ones that were never recorded. It also means seeing ourselves as more pliable: susceptible to these same defeats, and capable of new syntheses between us and these chaotic, ongoing and unfolding teloi.

Thinking…

On Syria. I find myself surprisingly numb to the fall of Assad. He’s gone. Good. He is a vicious, authoritarian monster who tried to drown every inkling of democracy in blood. A more just world would have him sitting in the dock at the Hague rather than cavorting round Moscow. That his brittle regime fell so easily after all this time attests to this. Celebrations are warranted. Not that any of the countless who have lost family and comrades, or the thousands of prisoners who have spent years being tortured and starved, need my sign-off.

In another respect, the joy around Assad’s fall feels like a faint echo. I am not the only one who feels it like this. Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen, Syria: these were places that, fifteen years ago, piqued hopes around the world for people who’d had the bottom dropped out from under them by the 2008 crisis. They provided the beginnings of a schematic for something better, an actual alternative. Those of us who had been around for the global justice movement ten years prior were excited to see some veracity brought back to the idea that another world is possible. That it was the Arab world putting it in practice, pushing back on a decade of War on Terror Islamophobia made it all the more poignant.

Looking back on these revolts now drums up a distinct mix of pride and regret. Pride because of the above. For many of us, it felt like our 1968. Regret because we failed. Yes, in the telos of socialism and liberation, all failures should be seen as temporary. We don't have a choice. But we still failed. So did all the upsurges that came out of ‘68.

In Egypt, the fall of Mubarak led to democratic elections and a flourishing of popular protest before El-Sisi’s coup. He’s been in power for ten years, and his rule hasn’t been much different from Mubarak’s. Many Tunisians fear, not without reason, that current president Kais Saied is simply a new Ben Ali. Yemen’s civil war has transformed the country into a charnel house. Israel’s pulverizing of Gaza plods along; it’s extended into Lebanon, and now, further into Syria’s Golan Heights.

So yes, the ouster of Assad can only be a good thing. But the context is starkly different. Many of the diasporic Syrian left seem to feel the same way. In all the various factions now angling for control, the lack of a strong and vibrant left is noticeable. A notable exception is in the Kurdish northeast, though even its radical democratic experiments have foundered for some time thanks to its internal contradictions and external isolation. Given the patronage of Turkey, it is highly unlikely that Hayat Tahrir al-Sham will simply leave the Kurds be. Ultimately, we have no idea what comes next. It highlights how big of a watershed moment this is for the Levant and the Middle East. Jamie Allinson of Salvage has some words about it that are far more incisive than mine.

More on Luigi Mangione. I’ve said most of what I have to say on the matter in this post from earlier in the month. In that piece, I allude briefly to how Mangione’s arrest will complicate the narrative of those sympathizing with him. That’s happened, but in a manner far stupider than what I predicted. It’s rather pathetic to see Fox News, Marjorie Taylor Greene and Ben Shapiro paint Mangione as some Marxist wacko when his very syncretic beliefs were so amply broadcast after his arrest. I’m not sure how effective it’s going to be in hiving off sympathy with him.

I’m also not sure it matters that much. This whole episode has been notable for how divergent most arguments in the mainstream media are from the broad sympathy Magione has elicited, and yes, that sympathy spans the political spectrum. But the past several years have shown how little public opinion matters when the right is able to construct even the most tenuous narrative against something. It matters far less in terms of the outcome of Mangione’s case and far more for the people who identify with him and are already political targets. The left already has a huge target painted on it, particularly on college campuses. All the more reason to go onto the offensive, to politicize this moment. To argue – if you’ll excuse the flagrant sloganeering – that the healthcare system should be on trial.

More on Wicked. Wicked is a reimagining of The Wizard of Oz, a kind of alternate history of the tale. But what of the alternate-alternate histories? What I mean by this confusing question is that from its inception, all of the Oz properties have been highly mediated ruminations on the notion of utopia. To reinterpret them – be that through film or further books (original author L. Frank Baum wrote 14 in total) – is itself to unavoidably add something to this contemplation. And it is one of the reasons that the story of Oz continually returns to the cultural landscape, from the beloved 1939 film adaptation through to today.

To reimagine is a necessarily utopian act. It starts with the idea of creating a world discrete from our own. Baum’s ideas about how the world “should be” were at best contradictory: he was a broad populist and women’s suffragist who voted Republican and occasionally defended the genocide of the indigenous. Gregory Maguire’s 1995 novel Wicked (on which the musical is based) builds on Baum’s tropes and ideas and reworks them to home in on themes of conformity and repression.

You could argue – and many have – that these kinds of subversive reinterpretations are there in the best-known reimaginings of Baum’s universe. The lyrics to “Over the Rainbow” were written by socialist librettist Yip Harburg. Dorothy’s family’s struggling Kansas farm – and the desire to escape it – was bound to read a very specific way in 1939 at the height of the Great Depression and with the Dust Bowl in very recent memory. In other words, there is something very particular and very interesting happening with the film Wicked that far supercedes what is happening in the film or its source materials, that contrast the 20th and 21st century notions of utopia running parallel to “the real world.” I’m not sure a full essay on the matter is merited (or particularly interesting) but my interest is piqued just enough that it might be the center of a future writing project. Of some kind. Maybe.

Header image is from Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979).