Pacts of Memory (Iberian Daydream, final part)

An homage to Catalonia, by way of tourist guilt.

For most of November, I was on my honeymoon in Spain and Portugal: Porto to Lisbon, then to Seville and Barcelona. I took the opportunity to try my hand at travelogging. The initial hope was to have this entire series completed in the first days of 2025, but disaster intervened. It has taken some time to return to completing the experiment. The results – found here, here, here, here, and below – have been enjoyable to write. Hopefully they’ve been enjoyable to read. If not, then good news: we’ve come to our final city: Barcelona. Wide open boulevards. Syndicalist bars. Fractured histories. Finally, do subscribe if you haven’t already.

XXIV.

Barcelona isn’t Paris. Paris had Baron Haussmann. Five years after the 1848 revolutions, he was appointed by Louis Napoleon to redesign the city. From 1853 to 1870, Paris was completely renovated. Its slums were emptied, the city center opened up. Gone were the narrow streets that made the construction of barricades easier.

Many suggest that the wide boulevards were intended to tamp down urban insurgency. It didn’t work. The year after Haussmann was dismissed from his post, workers, small artisans, and ordinary Parisians took over the city and established the first revolutionary commune in history. Haussmann’s former boss Napoleon fled too.

No redesign like this ever took place in Barcelona. La Rambla has existed there since the 1500’s. It has always been open and airy, stretching a little over a kilometer from the Plaça de Catalunya all the way down to Port Vell and the Mediterranean Sea. During the Civil War from 1936 to 1939, when all the city’s factories were essentially run by their workers, La Rambla was regularly flooded by mass demonstrations. Red flags, rifles raised in the air, the whole splendid panoply. All of the dramatic scenes that Orwell described.

The headquarters of the Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista was a few hundred yards down the thoroughfare. Now the building is an expensive hotel. Nonetheless, Barcelona’s history disproves the wide-open avenue as a deterrent to urban revolt.

Barcelona isn’t Spain either. Not really. La Rambla reminds you of this. Seville wanted us to leave with the idea of Spanishness as a quintessentially traditional structure of feeling. The city’s primary pastime, as far as we could tell, is Catholic processions. We saw an unusually large number of locals wearing slacks and button-downs. That wasn’t the impression in Barcelona.

The city’s signs were in Catalan, then Spanish, and often not even Spanish. Below the massive billboards for expensive luxury brands bobbing over the street, La Rambla insisted on something chaotically grimy, cobbled together, defiant and independent. At the intersection of Plaça de Catalunya and La Rambla there is a monument to Francesc Macià, president of the Generalitat de Catalunya from 1931 until his death in 1935. Under Macià, during the Second Spanish Republic, Catalonia achieved autonomy and, according to some, got as close as it ever has to gaining full independence in the modern era.

Of course, if 2017’s referendum is to be believed, then Catalonia is indeed its own country. The final vote tally of that referendum was 92 percent in favor of independence, 8 percent for remaining part of Spain. Of course, the total turnout for that vote was only 43 percent. Because the decision to hold the referendum in the first place was boycotted by anti-independentist parties in Catalonian parliament, it was declared an illegal ballot. The National Police Corps and the Guardia Civil were deployed to physically prevent people from voting.

During forty years of Franco, the city was forced to be something other than what it naturally is. Speaking Catalan was illegal. The communists and anarchists and other workers’ organizations were driven underground or wiped out entirely. Barcelona remained a hub of shipping and heavy industry, but its horizons had been repressed, its people’s souls penned in. It remained relatively underdeveloped after Franco’s death and the fall of fascism.

That changed when the Olympics came in 1992, with requisite buckets of cash and redevelopment schemes. No longer was the city atomized by iron authoritarian heels. Thirty years later, it is difficult for many to insist it isn’t atomized once again, albeit by a different and sneakier force. If anything has been made apparent in the writing of this series of travelogues, it is that the city of modern Europe often confuses reification for memory, holding forth a city’s most distinctive histories and cultures in their most static form so that outsiders can gawk at it, wide-eyed and slack-jawed. And if that history is unfinished, as it so often is? If it wounds still itch? If its people are restless? The city of modern Europe doesn’t have an answer for this.

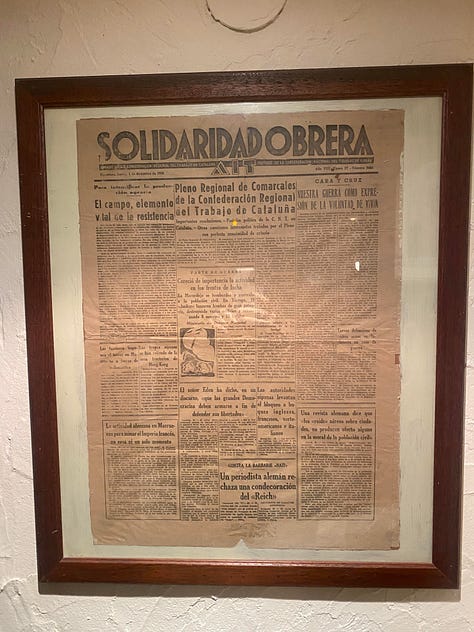

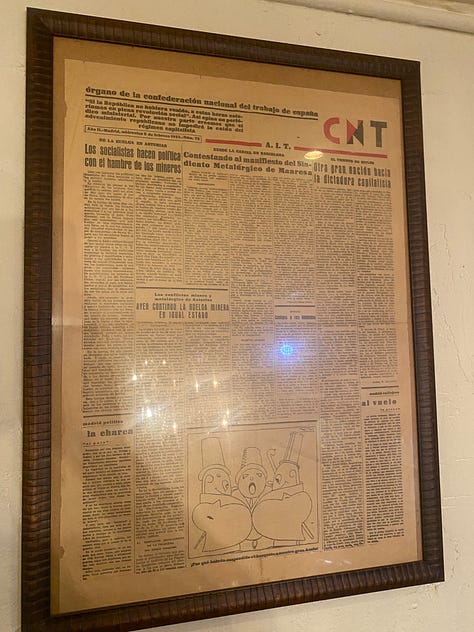

A few blocks off La Rambla, wedged into the narrow streets of El Raval, is Bar Llibertaria. Its drinks are cheap, its tapas are filling, and it was founded in the early 2010’s by a supporter of the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo, the anarchist trade union that played a central role in resistance to the dictatorship. As one might expect, the walls of Bar Llibertaria are covered in posters from the 1930s beseeching readers to join the CNT and resist the rise of fascism. Peasants and workers, often armed, smiling and broad-shouldered, drawn and painted in that warm, dusky light. Oranges, yellows, browns, blacks, various shades of red. The entryway has a painted statue of a young boy in a newsie cap hawking copies of Solidaridad Obrera.

Mrs. Daydream and I felt right at home. We ate, we drank, we talked politics with the bartender. We told her that the recent elections made us want to go home even less. She told us she was from Poland, where Andrej Duda ruled for nearly a decade before the current centrist government swung into power. She was well-acquainted with the havoc of the hard-right. It was why she came to Barcelona.

XXV.

I dislike Gaudi. This doesn’t make me all that unique, but many people who know me are surprised when I tell them. Part of my dislike is that, across timelines, there really isn’t anything all that special about his aesthetic. There’s no reason that the flowing lines and over-baroque ornamentation that characterize his work shouldn’t have become the standard in every city. There was nothing that should have made his work less architecturally ubiquitous compared to, say, Le Corbusier or Mies van der Rohe. We act as if the city is an intentional thing, that a coordinated set of choices guides it. Certainly there are choices made, but they just as often conflict with each other or take random twists and turns that make no sense concerning what came before. Only by sheer accidental happenstance do certain designers’ and architects’ aesthetics become widespread while others become curiosities and novelties.

Curiosities and novelties can be lucrative. Anything that sticks out enough can be enclosed with a rope and tickets sold to see it. Thus Gaudi, and what I dislike about him. Given his aesthetic, how easy it is to lump the merely whimsical with the strange and surreal, he is supposed to be fascinating to “people like me.” And when people who make money off tourists think of “people like me,” they think of us as children with money. Easily amused, constantly longing, but unable to remember much of anything.

The journey toward Park Güell was a rather long one. There are, of course, countless Gaudi houses scattered throughout Barcelona; most of them will allow you to walk around inside for about thirty euros. Park Güell is a large complex of parks, gardens, buildings and architectural elements designed by Gaudi and opened to the public in 1914. Spanning about 47 acres, it was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1984. Despite my dislike of Gaudi, it seemed like something we should see. Our challenge was that it was three miles from the city center where we were staying. We decided to walk.

We didn’t quite register two things. The first is that Barcelona can get very hilly. The second is that the neighborhood of La Salut, where Park Güell is located, is primarily residential and very working-class.

By the time we arrived, we had already been walking for some time. The hills we encountered when we entered La Salut were uninviting enough. Then we started to notice the apartment balconies. The number of Catalan flags was expected. The number of signs telling tourists to go back to the city center, or to simply go home, was less expected.

Barcelona hates tourists. As a tourist, I can confirm this is absolutely the correct stance to take. Nobody needs reminding of how annoying we can be, particularly if we’re American. The Olympics kicked down the door for a free market fundamentalism that, for the past three decades, has put working-class lives under economic siege and transformed wide swathes of the city into a commercial version of itself. There was a time when this kind of fuckery was seen as uniquely American, bound up with the particularly stupid and vicious United Statesian equation of anything the least bit uncommodified with communism.

Whether or not that was ever a fair equation is beside the point now. We know the model has thoroughly transformed the social spheres of every western European country and virtually any nation friendly to the United States. It’s happened in China and Russia too, just through somewhat different mechanisms, but the thrust is the same. Barcelona simply had the misfortune of facing to the west.

Throughout this entire trip, I found myself wondering what a different model of experiencing another city might look like; one that isn’t premised on turning every home into a hovel and every neighborhood into a destination.

I can’t say I’ve come up with one. Though it does seem that travel conceived as a luxury, a practice that assumes safe and conspicuous consumption, is bound to homogenize and erase. We might have thought ourselves different from your typical American tourist; thoughtful, curious, courteous, left-wing, sensitive to history. These attempts were probably no match for our vocal fry.

The ire of Park Güell’s neighbors is justified. When we finally arrived, it was mid-afternoon. The park was already teeming with the shrill touristic bedlam: kids crawling over the architecture, exhausted parents glad to have a moment that their children aren’t whining about being bored, hordes of people stumbling over each other for a picture. In the background, the sprawl of Barcelona: skyscrapers and spires, antenna arrays, ancient ruins weaving through modern neighborhoods reaching over hills. If I lived here, with all these layers of history blooming up from the ground in front of me, and I had to compete with braying gaggles of the hapless, I too would be well beyond frustrated.

We did not have the opportunity to add to the swarm. By the time we arrived, it was mid-afternoon. Somehow we hadn’t clocked that the park limits the number of people that can enter on any given day. The park was full, and no more tickets were available. Serves us right.

XXVI.

Park Güell is close to the edge of the Serra de Collserola mountain range, right as the urban sprawl gives way. To get to Castell de Montjuïc, we had to cross town, all the way to the Mediterranean coast. The foundation stone for Castell de Montjuïc was laid in 1640. The next year, the Catalan Revolt against Spain kicked off, and the castle saw its first battle.

Since then, the castle’s stolid corridors and courtyards have been something of a weathervane for the fortunes of Catalanisme, between independence and Spanish domination. From the top of Montjuïc hill, you can see not only the practical whole of Barcelona, but the city’s massive port, a crucial nexus of cross-Mediterranean trade for some several thousand years. Thanks to the castle’s position, it can be used to either defend or bombard the city. There is a distinct sense that they who control Montjuïc will be in control of Barcelona, and therefore wield decisive influence over the Iberian Peninsula.

During the Civil War, the republicans installed massive anti-aircraft guns to protect the fortress against Italian air attacks. After Franco’s victory, they became a reminder of both defeat and the seeming impregnability of Spanish fascism. Lluís Companys, the left-wing regional president of Catalonia during the Civil War, was executed at Montjuïc in 1940, and there is a small memorial dedicated to him near the castle’s moat. Countless republicans, anarchists, communists, socialists, and trade unionists were tortured and killed here. In 1963, Franco converted the castle into a military museum.

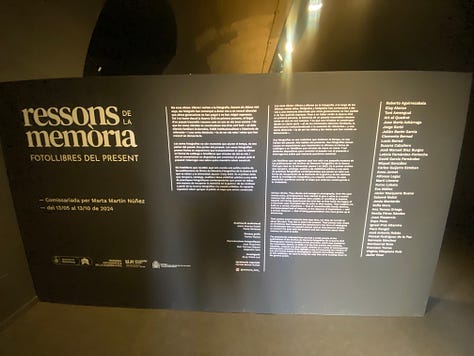

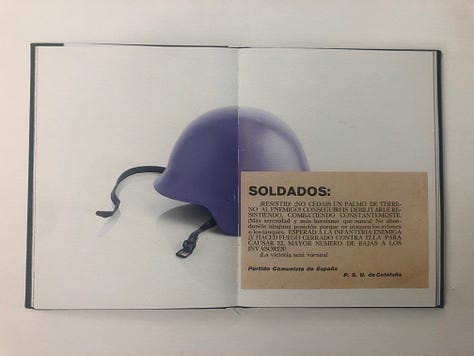

Today, Castell de Montjuïc functions as a municipal center. It hosts concerts and exhibitions. Our bartender at Bar Llibertaria had recommended an exhibit here of photographs related to state repression in the Franco era. It was, naturally, difficult to take in. Testimonies of torture, executions, rape, loved ones abducted by police. Women could be arrested and imprisoned for simply being related to anyone suspected of being a red. Some 12,000 children of republican parents were taken from their imprisoned mothers and shoved into orphanages where they would be essentially indoctrinated by the state. The brutal execution of Federico Garcia Lorca, perhaps Spain’s greatest 20th century poet and playwright, is mentioned. So is the Stanbrook, the English cargo ship that took the last 3,000 republicans who were able to flee as the republic fell in 1939.

Here I learned that “the right to memory” is actually enshrined in Spanish law. The 1977 Amnesty Law that allowed Spain to transition to democracy after Franco’s death has often been called Pacto del Olvido, or “the Pact of Forgetting.” The brutality of the Civil War, and of Francoist fascism, went unaddressed. Torturers and executioners were unpunished. The disappeared remained the disappeared. Mass graves went untouched. So did public fascist symbols and street names.

The Ley de Memoria Histórica of 2007, passed over the objections of the conservative Partido Popular, sought to rectify this. The government dug up the mass graves, attempting to identify remains and provide restitution to the victims’ families. Coming to power in 2011, the right-wing PP government of Mariano Rajoy sought to essentially strangle the Law of Historical Memory, slashing its funding by 60 percent.

After the center-left PSOE returned to power in 2018, Franco’s grave in the Valley of the Fallen (just outside Madrid) was moved. Though Spain’s parliamentary social democrats are broadly in line with those around Europe – dedicated more to the idea of a humane market than anything resembling workers’ power – it would be wrong to say that the relocation of Franco was a sign of respect to the dictator’s descendants. The Valley of the Fallen has long been a site of celebration for the far-right, a place where the bodies of 30,000 executed republicans and leftists had been moved without their families’ knowledge into one of the world’s largest mass graves. Franco’s tomb was one of only two ever marked. The other was José Antonio Primo de Rivera, founder of the Falangist Party.

A monument built on a literal mountain of bodies. Though Franco is now interred in a private family plot, the 490-foot cross still stands, as does the basilica, bigger than St. Peter’s in Rome. Compared to this, the exhibition at Castell de Montjuïc could only be understated, memories that speak plainly for themselves, without adornment or embellishment. It is almost as if fascism believes that any memory untriumphant in timbre isn’t worth commemorating. Yes, fascists exiled from power love to cite examples of their fictional victimhood, but after they conquer, these days become occasions to thump their chests and bellow victory. What, exactly, becomes of memory, in all its whispering contradictions, when this regime prevails?

XXVII.

You can understand why, as the Portuguese Revolution unfolded, Henry Kissinger so openly feared it. The rise of workers’ and soldiers’ councils in Portugal was the spearpoint of a broader context. Greece (where the generals’ junta had just fallen) and Italy both had strong and militant far-lefts. There was Tito’s Yugoslavia, whose repeated attempts to build a socialist model separate from Soviet influence made the country something of a wildcard. That Franco’s regime was teetering wasn’t particularly surprising – he was, like the Portuguese Estado Novo, isolated and geriatric – but it did put a question mark over a key US ally.

The material of this Red Mediterranean was on all sides of the sea. Libya had declared itself socialist (albeit a highly religious, idiosyncratic, and ultimately authoritarian variety). Memories of Algeria’s struggle for independence barely a decade before, as well as its more recent experiments with workers’ control, also got western observers’ hackles up. In this context, it is worth remembering how many historical empires did not differentiate in the way we do between the Mediterranean’s northern shores (Europe), southern shores (Africa), or eastern shores (Levant). These different regions weren’t separated by the Mediterranean but brought together by it.

However incorrect it may be to view the Mediterranean as the center of the world, it was understandable for pre-capitalist empires. Without access to this sea, global trade was severely hindered. For Rome, Macedonia, Constantinople, empires and dynasties alike, the Mediterranean was the horizon.

Empires change geography, but so do revolutions. Or, more specifically, they change our conceptions of geography. The idea of a socialist Mediterranean, of the gate between Africa, Europe, and Asia turned red on all sides; this would shift the fortunes of a late capitalism already reeling from the collapse of the postwar boom. The same for an imperial order bogged down in Vietnam and reviled by insurgent people the world over.

A different timeline comes into focus; different memories, different pasts colliding with the present, producing different futures. It didn’t happen, but it was in the cards. We can see here, in this brief “what if,” the material consequence of memory. If history were simply one thing after another, then the right to memory wouldn’t matter. But when we see history rather as a series of contingencies, each moment pulsing with different potentials, this right becomes urgent, sacred even. Empires carve a path for memory, shifting and blocking its direction. Revolutions unleash it, allowing it to touch down wherever it might. Its previously solid barriers become flimsy and pliable.

XXIII.

Yes, the ‘92 Olympics turned Barcelona into a “global city,” a city that was on everyone’s map, a place whose culture was fit to be experienced by people from around the world. The Soviet Union had imploded the previous year, and the only language available for global community was that of the market, of commerce.

It remained that way even through the financial crisis of 2008 and Spain’s economy neared total collapse, along with the other economies of Mediterranean Europe. The European Central Bank, notoriously, shamelessly, demanded more pain from the PIIGS nations to pay off their debts. Living standards still haven’t recovered.

Then came Covid, leaving every city still and silent. The explosion in tourism that followed made Barcelona one of the top three most visited in Spain. From the sound of it, the streets started to swarm with gawping boors who would be as annoyed as any Catalonian if their own city became not theirs. Some studies found that there were neighborhoods where almost half of all residential units had been turned into short-term rentals.

In the early months of the pandemic, architect Massimo Paolini penned a “Manifesto for the Reorganisation of the City after COVID-19.” This was, essentially, an attempt to map a degrowth Barcelona. Its demands were broad, but reigning in tourism played a large role. Ban cruise ships from the city’s ports. Freeze the expansion of the airport. Reject the building of museums explicitly aimed at tourism. Cease city investment in building the Barcelona “brand.” These work in tandem basic Right to the City demands like expansion of green spaces, the decommodification of housing, and the lowering of rents.

This last point was the central demand of the demonstration we encountered on our last night in Barcelona. We had seen these fliers posted from the minute we showed up, but only after seeing them several times a day did we bother translating them. S’ha acabat… Abaixem els lloguers. “It has to end… Let’s lower the rents.”

Sure, the fliers were hard to miss, but we had no way to know how big this demonstration would be. We found out coming back into the city center from Montjuïc. It was easily between 100,000 and 200,000 people, thrumming through the wide streets of central Barcelona. Loud, militant, banners of tenant groups and labor unions, a smattering of Palestinian flags, as well as flags of several far-left groups.

One of the hardest to miss among these flags is a red and black one with the initials of the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo. It was their posters that covered the walls of Bar Llibertaria. They have a long history in Catalonia generally and in Barcelona in particular.

Whatever criticisms one has of anarchism — and there are plenty, including one we’ll get to presently — the CNT continues to have a following because of its unwavering defense of radical workplace democracy. This didn’t prevent them from making one of the most maddeningly tragic blunders in revolutionary history during the height of the Civil War. Seeing their influence, and believing in an independent, socialist Catalonia, President Companys approached the anarchists during the war’s height and did what virtually no bourgeois elected representative has ever done: he offered to hand power over to them. Parliamentary rule would become direct democracy. But the CNT turned him down. Being the good anarchists they are, wielding power didn’t become them.

One group that definitely loves to wield power? Fascists. And despite the idealist protestations of anarchists, anti-power never bests power. Things fell apart after Companys’ offer was rebuffed. The left antifascist coalition fractured. Moscow ordered the Communist Party to turn on their allies. Barcelona fell. Companys fled to Paris. Eighteen months later, France was in the hands of the Nazis, and Companys was sent back to Spain where he was executed at Montjuïc.

Still, the CNT survived the Franco years, and the fall of the Soviet bloc. At one glance, these flags represent the durability of revolutionary ideas. At another, the catastrophic failures that smothered the promise of a Red Mediterranean and haunt Barcelona. A Barcelona that stepped onto the world stage thanks to the commercial spectacle of the Olympics, or one that provides for its residents, offering them the chance to remake the city and themselves. Memories of what was, and what could have been.

I know which city I want to visit. I also know which one actually exists. All I can plead is that if we go to these places only to see what exists, then we sell short both ourselves and our destination.

All photos by Kelsey Goldberg and the author.